We often forget that many of our favorite games were developed by foreign studios and scripted in languages other than English. Non-English speakers, however, are far more aware of the work that goes into bringing a game to them from abroad. Translations are a crucial, but not well-understood, aspect of game development. Synthesis is a worldwide group with offices in a dozen countries that focuses on video games localisation.

Tiago Kern, a native Brazilian with a journalism degree and fluency in English, works in the Brazilian office – mainly as a proof-reader and sometimes translator for Synthesis. He sat down with me to discuss this vital aspect of game design.

GS: So how and why did you get into translating, and video game translating in particular?

TK: I’ve been studying English since I was a child, as my father used to be an English teacher in his youth. I’ve always liked reading books and playing video games, and – especially with games – we never got the translation for many games in Brazil. In fact, I think I learned a lot of my English just from playing video games in English as I grew up.

I started working with translation informally. I’d offer translation services in the ads of a local newspaper, and that got me my first job as a translator for an Intellectual Property company. I made the move to video game translating some time later when a friend of mine mentioned my name when his teacher asked if he knew someone who played lots of video games and was proficient in English. This teacher must have given my contact information to Synthesis, as I was contacted by them some months later when they were starting to set up their Brazilian team. I had to take tests devised by the company and go through a training phase, and now I’ve been working for them for almost four years.

Synthesis localizes numerous games for the Brazilian community

GS: What games did you play growing up and what is your overall gaming background prior to translating?

TK: My father got me an Atari system in my early childhood, and from then on I kept playing: I had a NES, then a Mega Drive (Genesis), then a PS1 and so on. I was very fond of the Sonic the Hedgehog games when I was little, but I truly fell in love with video game narratives with Chrono Cross and Legend of Legaia in the PS1. Everyone mentions the Final Fantasy games on the SNES and PS1 as their “gateway” JRPGs, but the first Final Fantasy I completed front to back was actually Final Fantasy X, so I guess I jumped on the bandwagon a little too late.

GS: So first of all just talk me through the basic process of translating a game.

TK: Well, it really depends on the client you’re dealing with. We usually receive chunks of text from the game and translate it gradually – as sometimes the full scripts are not even completely written by the time a game’s localization process begins. There are usually separate files for the dialogues and script, the menus, the button prompts and everything else. The client usually sends us reference files for us to check and study in order to translate the game, but it’s never enough, and the effort that the client puts in to answering our questions (whether they have a fulltime Q&A team or not) is a giant factor for the overall quality of a game’s translation.

Once the text that needs to be recorded is fully translated, it is sent to a studio and recorded with Brazilian voice actors. If they make changes to the text during the recording sessions, we are notified and then implement the changes into the game’s text (usually this happens due to time constraint and/or lip sync for character lines).

GS: How much freedom do you have when making a translation? Can you make changes that you deem necessary or must you stick to direct translations?

TK: Video game localization infers that you will need to adapt the game to your language and to your country’s gaming public. Our goal is to translate the text to the best of our abilities, trying to convey the original message to the Brazilian players, but some things change during the course of localization.

For instance: if there is an acronym in the original game and there’s no way we can use the same acronym for a translation in Brazilian Portuguese that retains the same idea, we may change the acronym in the translated game – provided the client says it’s fine, of course. The same goes for puns and jokes: some things are impossible to carry over, as English puns will simply not work in Portuguese, so we must come up with a solution – a pun of our own, or an adaptation of the original text with new ideas that will work for Brazilian Portuguese.

Certain things like puns simply can’t be translated

GS: I notice that you refer to the work as localizing the game rather than simply translating it. Do cultural differences between Brazil and the game’s country of origin ever effect your work?

TK: Not really… During the process of translation for Valiant Hearts, the other languages could offer some real input on their countries’ role during WWII, but Brazil remained neutral throughout all of this, only siding with the Allies at the end of the war, so in this particular game we noticed how we have a different background to the other languages in Europe.

What has happened more than once actually which showcases the view of foreigners of Brazil is this: we’ve been asked to translate games into “Neutral Portuguese”, so that it would be a translation for both Brazil and Portugal. But, as it happens, European Portuguese and Brazilian Portuguese are completely distinct from each other: from spelling to sentence construction and other aspects.

GS: So if not the cultural changes, what are the biggest challenges that the translation/localization team is faced with?

…people aiming to work with video games localization should not only be translators but also gamers.

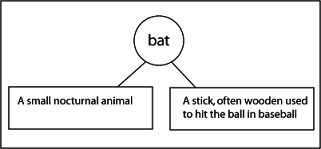

I guess the biggest challenge for a video games translator is to find a solution for tricky scenarios, where the original text is confusing or when it lacks context. Sometimes the same word may be used for six different things in English, so it has six different possible translations in Portuguese, and we get only this word and nothing else to go on. That’s one of the reasons why people aiming to work with video game localization should not only be translators but also gamers – if you do not play games, you won’t know how some terms are employed within games and will assume they refer to something else.

It’s true. Imagine what could have happened to Batman

GS: So context or lack thereof is probably the biggest challenge the team faces. To what extent do you collaborate with the original writers to combat this?

TK: There isn’t much in the way of the localization team collaborating with the original writers, as the writing process of a game is usually finished before we receive the text to localize. However, the final product of a localized game is certainly the sum of a collaborative work: some clients actually go as far as working with the development team in order to add new text to the game as a way of dealing with localized languages’ particular aspects: for instance, if the game allows for character creation, sometimes the game developers will be able to create separate lines that are spoken to or by the male or female characters.

This usually isn’t a huge deal in English, but in Latin languages like Portuguese, it is very hard to localize a game where the player can choose to play as a male or female character, since our adjectives will mostly have gender indications. So if the game developers allow for this kind of variation in the localized languages, a female warrior will be guerreira (instead of guerreiro) in Brazilian Portuguese, but if the localisation team has no support from the development team in a game like this, we’d need to go with a neutral term in Portuguese, such as combatente.

GS: What are the biggest project you have worked on and what work are you the most proud of?

I think the projects I’m most proud of are The Witcher III and Child of Light.

TK: Depends on what you’d call “big”. I’ve worked on several projects, some of which I can’t even discuss, but I’ve worked on Ubisoft’s Far Cry 3 and CD Projekt RED’s The Witcher III: Wild Hunt, which were definitely big games. I think the projects I’m most proud of are The Witcher III and Child of Light. Child of Light was particularly tricky as the original text was comprised of poems that rhymed, so the translation process for this one was a real challenge.

GS: You worked on the Witcher III from the English text? So the Portuguese has gone through two filters. How does that affect the finished game? Did you consult the Polish original as well?

TK: I worked as a proofreader for The Witcher III, but yeah, we translated the text directly from the English. In the translation files we were given, you could see the English text as well as the original Polish, so if you knew a bit of Polish I guess you could consult the original text – but I doubt anyone from our local translation team in Brazil would speak Polish. I did have the original text translated online once or twice out of curiosity. I’ve read the three books from The Witcher that were translated from Polish into Brazilian Portuguese (by Tomasz Barcinski), since the books were taken as the main reference we had for the project. That being said, some of the names in the game were changed, as the English version used some different names for characters: for instance, “Dandelion” is “Jaskier” in Polish and in the books, but we used “Dandelion” in the games, just like English.

GS: You mentioned working on Child of Light and its rhyming structure. I have often wondered how things like Shakespeare can be translated. How on earth can you keep both the meaning and the rhyme when localizing the game?

TK: We were told to keep the rhymes as long as it didn’t sacrifice the meaning. We also had length contraints for each line, so it was quite hard to localize this particular game. Sometimes we forgot about the rhymes yes, but I tried to rhyme as much as possible in-game. There are probably very few verses where there are no rhymes in the Brazilian version.

Poetry is particularly difficult to translate

GS: English speakers often forget that translators are even a part of game development. We forget that any Nintendo game we ever play was actually translated from Japanese! How do you think the experience of playing a game is effected by playing it in its non-original language?

TK: I think playing a game in its non-original language is great provided that there was genuine effort in the localization process. Video game localization is kind of a weird thing still: with movies, you get to read the script and sometimes watch the movie, and then translate the dialogue and subtitles; with books, you have the whole thing right there, there are no accompanying visuals; but with games, it all depends on the interaction between the client and the localization company, and on the familiarity that the translation team has with the game’s genre and mechanics. Sometimes you get amazing localized versions of games, and sometimes “you must defeat Sheng Long to stand a chance…”

GS: “You must defeat Sheng Long to stand a chance!” Any funny stories about mistranslations or anything like that which made it into a game you worked on?

The original text read “Pull the trigger” and the translator inserted a typo in Portuguese so that it read “Aperte o gatinho” (“Pull the kitten”).

TK: I’ve heard stories about terms that have been translated erroneously in games to great comedic effect, but no particular one I can think of right now. However, I do remember that once I was proofreading a batch for a game where the original text read “Pull the trigger” and the translator inserted a typo in Portuguese so that it read “Aperte o gatinho” (“Pull the kitten”). Of course I laughed when I read that, but ultimately I corrected the text.

GS: Do you play the games you translate?

TK: It depends on the game. I’d like to play them all, sure, but most of the time you don’t get a free copy of the game you’ve worked on – although that does happen every now and then. Of course, I’d play the games if they appeal to me. I’ve played many games where I was part of the localization team. I have not played The Witcher III yet (I ordered it already, but it didn’t arrive yet), but I put a lot of effort into this game, so I can’t wait to finally play it and see the final results.

Need an excuse to play The Witcher III again? Check out Synthesis’ work

GS: Any advice for bi-lingualists out there who might want to get into your line of work?

TK: I find that usually people who wish to work in the localization process for video games are either amazing gamers who know little English or make a lot of mistakes in Brazilian Portuguese… or the other way around: people who speak English perfectly and know how to deal with Brazilian Portuguese grammar and adaptation but who rarely actually sit down and play games.

I think the best advice to hone your translation skills for video game translation is to actually play games both in the original language and in the localized languages: check how they dealt with each issue, see if you can find translation mistakes, pay attention to how text is displayed in the game and what solutions they found for challenging situations. Play games from different genres and see how the tone changes in the language: some games have extremely informal language, others keep their text safe from curse words and slangs.

And finally, take part in localization events, such as LocJam, since that helps a bunch – it helps you get to know people who work in the industry while at the same time you discuss the process of localization, its challenges and practices.

A huge thank you to Tiago Kern and Synthesis for facilitating the interview. How many of you out there have ever played the same game in more than one language? How aware are you when you play a game that has been translated for you? Comment below to ask Tiago any other questions you may have.

Published: Jun 26, 2015 07:53 am