We live in exciting times for video games. AAA games are getting bigger and bigger every year. The indie scene is booming, offering a wide variety of new play experiences and giving anyone the chance to make and sell their own games. And researchers are investigating the benefits and potential therapeutic uses of video games, developing new technology that pushes the boundaries of what games can do for us.

One of the more promising techniques video games are being used for is “brain training,” which is exactly what it sounds like. Companies that specialize in brain training claim that it can help people control focus and concentration, improve memory, reduce stress, learn faster, and more. Sound like a lot to promise? Maybe, but some experimental games are living up to the hype.

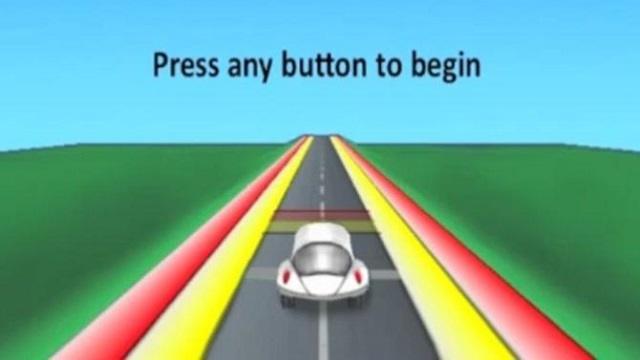

Dr. Adam Gazzaley, psychiatrist and founding director of the Neuroscience Imaging Center at the University of California in San Francisco, is among those exploring the brain training potential of video games. He and his team began by developing NeuroRacer, a game designed to improve users’ multitasking skills by controlling an animated racecar while reacting to signs along the road, pressing a button if the sign is green and doing nothing if the sign is blue or red. (No word on what red-green colorblind participants were supposed to do.)

In a paper published in the journal Nature, Gazzaley and the rest of his team presented the impressive results of their NeuroRacer study:

Here we show that multitasking performance, as assessed with a custom-designed three dimensional video game (NeuroRacer), exhibits a linear age-related decline from 20 to 79 years of age. By playing an adaptive version of NeuroRacer in multitasking training mode, older adults (60 to 85 years old) reduced multitasking costs compared to both an active control group and a no-contact control group, attaining levels beyond those achieved by untrained 20-year-old participants, with gains persisting for 6 months. Furthermore, age-related deficits in neural signatures of cognitive control, as measured with electroencephalography, were remediated by multitasking training (enhanced midline frontal theta power and frontal–posterior theta coherence). Critically, this training resulted in performance benefits that extended to untrained cognitive control abilities (enhanced sustained attention and working memory), with an increase in midline frontal theta power predicting the training-induced boost in sustained attention and preservation of multitasking improvement 6 months later.

For those of us who don’t speak jargon, what this basically means is that after playing NeuroRacer for the study, 60-85 year olds were able to outperform untrained 20-somethings when it came to multitasking, and the benefits were still measurable even 6 months after they stopped playing the game. Additionally, the game unexpectedly improved participants’ working memory. Pretty promising stuff.

Following NeuroRacer, Gazzaley co-founded Akili Interactive, a company seeking to develop games that could treat depression, ADHD, and other mental illnesses and disorders:

At Akili, we’re in the process of building clinically-validated cognitive therapeutics, assessments, and diagnostics that look and feel like high-quality video games. Our aim is to develop a new type of Electronic Medicine™ that can be deployed remotely directly to any patient anywhere, prescribed and tracked by physicians, with the potential to be developed at a fraction of the cost of traditional medical approaches.

So, are we approaching a day when specialized video games may be prescribed in place of medications like Ritalin and Adderall? Greg Toppo, author of The Game Believes in You: How Digital Play Can Make Our Kids Smarter, seems to think so. In a published excerpt from his book, Toppo looks at how Gazzaley and others are changing the ways we view and use video games. He closes the segment with a thoughtful quote from game designer Robin Hunicke:

We are at a place right now where this medium has the opportunity to expand in drastic and amazing ways. And if you are a designer, I would hope that you’re curious enough to really push on that boundary and not just accept the status quo, not just work on a game because you know it will make money, but to really push yourself in your craft to design something new.

While video games’ entertainment value is well-established, it’s exciting to see all the new possibilities this research is opening up for the medium. Maybe someday soon, video games will be seen as a valuable therapeutic tool – one people will actually look forward to using.

Published: Dec 3, 2015 01:07 pm