There’s a lot of decrying these days for games that add filler content, just as much are there are complaints for those that don’t have “enough” content like The Order: 1886. One of the most hated aspects of games with filler are backtracking sections where you must traverse a level you’ve already gone through before. I’ve thought a lot about this, and I’m beginning to question if we’re looking at things the wrong way.

What is Backtracking and Why is it so Horrible?

So, say you’ve never played a game with backtracking — what does that mean? Well, it would mean the levels never go back to any previous rooms and/or set pieces you may have participated in before. Every part of the level design forces you forward, and you can never go back.

If your mind is thinking back to NES-era gaming, you are on the right track. Mario in particular forced you to never go back, and always keep moving forward. While you could go back an inch or two, you really couldn’t go back and try again for that 1-UP block or get all the coin boxes you missed.

Now, take a game like Halo: Combat Evolved, where on several occasions you walk back the way you came and/or reused path ways to reach new areas of levels. One level in particular is a reversed and expanded version of a previous level in the game. When Halo: Combat Evolved: Anniversary released, it was criticized for this. In particular, in Game Informer’s review, Matt Miller wrote:

Unfortunately, because the gameplay has been left unaltered, players are also stuck with some of Halo’s less fondly remembered features. Disastrous checkpoint placement can regularly derail the fun. You’ll backtrack through almost every level in the game at some point. Shields recharge slowly, and the health system regularly leaves you badly damaged right before a big fight. The lack of objective markers will often have you searching through empty corridors long enough to push your patience to the limit. We were more accepting of these flaws a decade ago, but time and advancing design make the frustrations more noticeable.

Now for comparison, a review by Eurogamer of the original 2001 release:

The one downside to this heavily scripted story-led malarkey is that the game is depressingly linear at times, shuffling you from one encounter to the next and rarely giving you any real choice in where to go or what to do. While running around space ships and Halo’s interior you will find an amazing wealth of locked doors which keep you from straying from the one true path, with occasional neon arrows conveniently painted on the floor to point you in the right direction in case there was any doubt. The outdoor settings look fairly open at first sight, but although there’s more freedom of movement there are still only one or two paths open to you most of the time thanks to steep-sided canyons and the occasional rock fall.

You see, as gaming has evolved, our priorities in level design have shifted. Once upon a time, a game like Halo: Combat Evolved was seen as too-linear, which is almost laughable now. Instead, now we’re complaining about it requiring us to explore its levels thoroughly and backtrack. This is the tip of the confusing iceberg when it comes to backtracking’s acceptance in the gaming community.

Bats, Dragons, and Inconsistencies

You see, this isn’t a problem exclusive to shooters and platformers. Even role-playing games like Dragon Age have had to grapple with this. Dragon Age 2 attempted to focus on a single city for its campaign, and as a result you often went through familiar districts, outskirts, and streets. It was heavily criticized by fans for this.

Responding to this, Bioware released Dragon Age: Inquisition not even a whole year ago, with two large regions to explore, on top of hours of unique story content. Now, Inquisition has been criticized for doing the exact opposite of Dragon Age II. Not all games have had a problem with this criticism though, and that’s where things get really weird and nonsensical.

Why is Batman here? Well, because Rocksteady’s Batman: Arkham series is, amongst other things, a Metroidvania game. The subgenre involves unlocking upgrades for greater traversal and combat options, a tightly woven yet large world to explore, and lots of backtracking. Somehow though, I doubt you’ve heard anyone complain about repeatedly visiting the Arkham Library or having to go back into Intensive Treatment at the Medical Wing.

This is where the criticisms start to feel awkward, as backtracking truly is something the Arkham games have leaned upon. Not only can you backtrack, but completing each entry to its fullest extent and several specific missions require you retrace your steps. And yet, Rocksteady’s gotten by pretty well with minimal complaint. What does this mean?

The Real Problem

You see, the problem itself isn’t backtracking. It’s both how the backtracking is executed, and modern gaming trends. On the former front, I feel Jon X. Porter at Venture Beat put it best, in his article Backtracking: You’ll Need the Blue Key to Read this Article:

What’s important about these games is that you never backtrack for a single-use device. Doom‘s system of red and blue keys is fine for its small levels, but when put into a larger game, such as the original Devil May Cry, it becomes not just irritating but unsatisfying to wade back through.

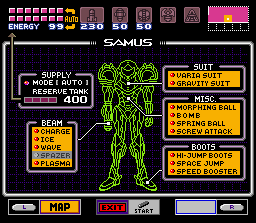

Contrast this with the previously mentioned Morph Ball from Super Metroid and the numerous places throughout the game where you can use it. It’s not just some throwaway item you immediately discard — it’s an essential part of your arsenal that you’ll use for hours to come.

Whenever we’re reintroduced to a level in a game, we need something new to keep us invested and interested. Some games like Alien: Isolation let us unlock new areas and obtain new gadgets, much like Arkham and Metroid. Other games like Halo 3 and Half-Life 2 use a consistent flow in their levels to give a sense of cohesion and making the levels feel like real places.

The best consistent flow games also change the scenario within their levels as you retread them. In Halo 3‘s level Crows Nest, as you defend a UNSC base, you face different enemies as the siege progresses and you run around the base helping your allies. You go from turret sections in wide hangers to tight corridors constantly, rarely given a moment to breathe. The level design in such games needs to be dynamic and flexible, supporting a variety of approaches.

The other part of the problem is that as games have progressed and yearned for being more like “cinematic” and being more “like a real movie”, we’ve stepped away from older styles of design that properly used backtracking. Shooter level designs were maze-like once, yet now games like Crysis 3 and The Last of Us are praised for offering us minor amounts of non-linear level design.

With games like Uncharted, Gears of War, and The Order: 1886, any ounce of backtracking can become an annoyance due to just how restrictive it can be. The more scripted the level design, the more a player has to follow what the designer intended instead of changing it up how they want. So then it feels more reptitious, and is far more obvious and lacking in fluidity.

The backtracking becomes more contrived, and doesn’t even have an exploration element to lean upon. Thus, it feels more forced than it already was. While some games like Batman: Arkham City find a happy middle ground, it’s clear a lot of developers still can’t find the right footing for this. Unfortunately, this is also impacting the latest generations of games.

For instance, in Techland’s Dying Light, while the open world offers you plenty of options, it’s linear sections are some of the worst backtracking in recent memory. This is especially clear during the climax, where you constantly are being made to retread through incredibly specific paths. These paths that might only make sense coming from one direction, but you have to go both ways regardless.

As much as we jest and joke about how developers design single-player campaigns, there’s a real issue here. Backtracking alone is not the solution to expanding modern level design, nor is it the lazy, corner cutting level design trick some take it to be. The problem is that we are seeing a marked decrease in proper backtracking.

When used properly, backtracking can be a great asset and add to the experience. We should praise games for doing backtracking right, along with criticizing those that do it wrong, as we would any other facet of a game. That way developers can improve it, instead of attempting to abandon it altogether.

Published: Feb 25, 2015 12:59 pm