Narrative-driven games, often incorrectly called walking simulators, have given me some of the most existential crises I’ve had. Having to deal with sacrifice in Life is Strange, learning that I just shouldn’t be a privileged white boy in Acceptance, or wondering if I should even be playing the game in the first place with The Beginners Guide, these are some of the best experiences I’ve had in games.

Narrative gold over gameplay

While many argue games are all about gameplay and fun, I disagree. Games are also about having an experience, sharing a story, expressing an emotion or idea, or existing as an art form. Narrative-driven games which do one or more of these succeed the best. No games are better at being narrative-driven than Life is Strange and Firewatch. While they don’t have the intricate gameplay of Grand Theft Auto 5 or Dark Souls 3, they both tell beautiful stories with simple interaction. But how do they do this?

Watch out for the fires, but watch out more for your emotions

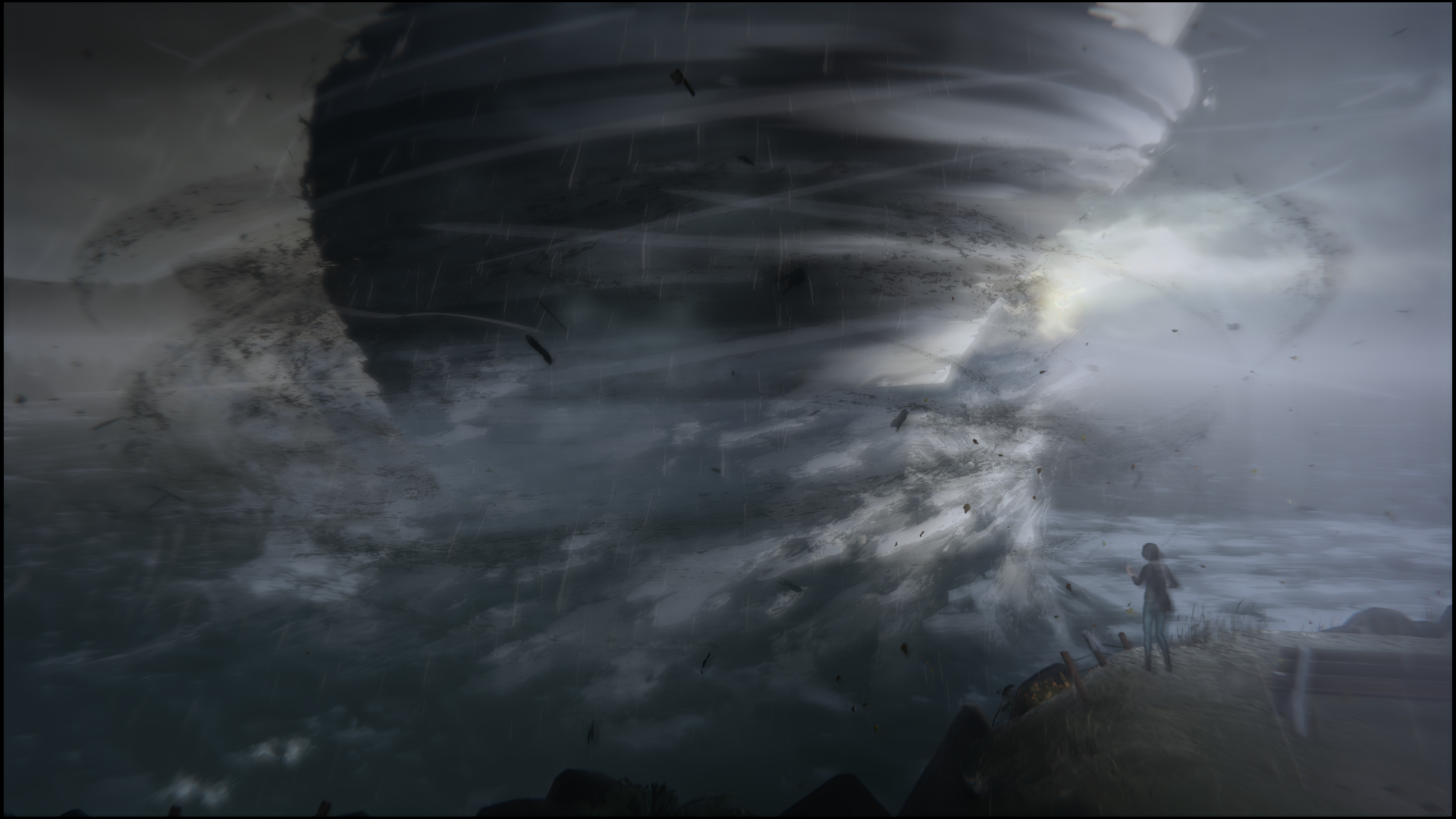

Firewatch, developed by Campo Santo, follows the story of Henry as a fire lookout in the wilds of Wyoming. Henry isn’t completely alone however, Delilah is on the other end of your only form of communication: a radio.

It’s this radio which sets Firewatch apart from what many call a “walking simulator.” You are not just walking around having things happen to you; you feel far more directly involved in the action, as if you are involved. Using the radio, you can talk to Delilah, or not. See something? You can tell Delilah about it, or not. You have real choices. Your relationship with Delilah can change depending on what you tell her, and the finale can completely change depending on how much you interact with her.

On the subject of interaction, Life is Strange is only about interacting

In Life is Strange, you play as Max Caulfield, a photography student at Blackwell Academy. Max discovers she can turn back time, this is the feature which takes Life is Strange from TellTale rip off, to something “totally rad.” — That’s something “kids these days” would say isn’t it?

Much like with Firewatch, your actions can affect how people interact with you, but with the addition of being able to turn back time. You can now creepily snoop around someone’s room — like you do — to find all the dirt you can on them, but now turn back time and effectively erase everything you have done from the other person’s mind. It allows for a “I did something you don’t know about” mindset. In real life that can lead to some very scary outcomes, but in the context of the game it can allow you to appease some very angst ridden teens and absolve them of their angst.

The term “walking simulator” get’s applied to any narrative-driven game. When this term is used for games like Dear Esther, The Stanley Parable, or even The Beginner’s Guide — which was my game of the year in 2015 — I can understand, as the interaction you have with those games is limited. Having said that, you shouldn’t because they are not simulating walking.

Having a journey through a world is a narrative. Take a look at books and films; they do not offer interactivity at all. A film is not called an interaction simulator, and a book isn’t a word simulator, so no game can be a walking simulator (unless it’s simulating the act of walking). If anyone were to say Firewatch is a walking simulator, I would refute that with the reasons provided above. There is a person and a world for you to interact with, even if the interaction is limited, you still make an impact on the people in that world.

These sorts of games should be called “narrative-driven.” There are some which give little interaction like The Beginners Guide, or the game which arguably spawned the genre Dear Esther, or those that give you a lot of choices for how you speak to characters such as the aforementioned Firewatch and Life is Strange.

These are the best examples of narrative-driven games, as they offer a near perfect balance of interactivity and story, but do you agree? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Published: Apr 5, 2016 2:00 PM UTC