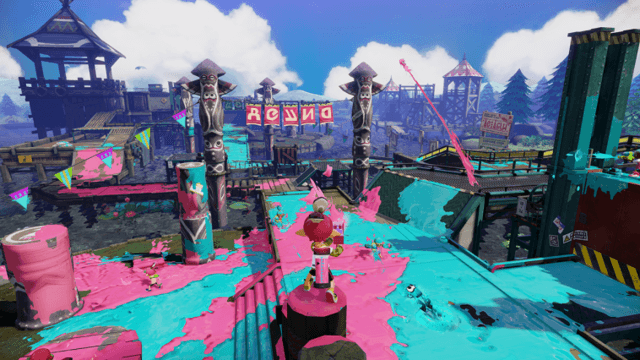

Matches of Splatoon conclude with a floor mirroring that of Nickelodeon’s Kid’s Choice Awards. Slimed, gooey, and vibrant. Oranges, blues, yellows, greens; this is an otherworldly aesthetic for a genre inundated with desert-friendly browns.

Splatoon takes this very traditional shooter genre and twists it in a very Nintendo way. Matches are sonically carried by the pitter patter of ejected ink blobs, not the bass of a rocket launcher. (Note Splatoon features rocket launchers, but they shoot dollops of splashy neon liquid. Everything does). Inklings fight in Ink Battles across the cordoned off interiors of Inkopolis – Splatoon has a thing for ink although it looks and moves more like paint.

An Inkling’s world is playfully punk-ish.

Eye liner, frazzled hair, unkempt shoes; each Inkling is as distinctive as Splatoon. Speakers stack on top of speakers in the Inkopolis‘ center, visibly throbbing to purposefully garbled metal and energetically scattered punk anthems. Posters are unevenly sorted on city walls and citizens stand underneath them, hands on their hips in a sign of teenage indifference. Whatever. Store employees bully (even cruelly) anyone not in their clique, a singular ounce of meanness in a video game which is otherwise welcoming. They must not need the business.

Inklings play a physical form of Midway’s classic Joust with illogically oversized paint rollers

This is a well-off society, though. They throw around the equivalent of $20 million worth of printer ink in a mere five minutes of combat.

Splatoon has its world, its color, its identity. No one here dies. They only pop and then respawn. Inklings play a third-person form of Midway’s classic Joust with illogically oversized paint rollers or coat their opposition with drops squirted from one of many decorated Super Soaker-esque weapons.

They’re not shooting each other, directly anyway. They shoot the floor. The walls. Maybe ramps and railings. If Ink Battle arenas featured a roof, Inklings would shoot those too, covering them in harmless globs of color. Splatoon’s goal is to be a shooter interactively realizing, “the pen is mightier than the sword.” The phrase was coined in 1839. In 2015, the words carry literal meaning.

Obsessive Compulsion

Miss a spot when painting a wall in the real world and the spot is all that can be seen. Splatoon is analogous to an enormous wall of fresh paint, only someone else is competitively making splotches of different colors – or circles or splatters or lines. Entire sections are covered in an example of cruelty against OCD sufferers. Prayers go out to the neat freak. Splatoon pings the worst components of compulsion.

Ink Battles are kryptonite to any perfectionist. The ink slips onto walls and colors venture outside lines. Splatoon is too manic to worry about the ideal look. There is a pretend sport to win where everyone receives a trophy. Experience, currency, or something will be doled out to all players no matter the end marks.

Splatoon doesn’t allow anyone to delve into statistics either.

It’s far too simple to be bothered by numbers. And no wonder: Five cycling maps, two modes, one town, one selectable loadout at a time, zero voice chat. The numbers sound awful and they are. Inexcusable, even. At least the servers work.

Splatoon’s pop-up, user-made messages in Inkopolis are bizarrely safeguarding of their chosen corporate monolith

Yes, Splatoon is at odds with all consumers know, nay expect. That’s very Nintendo. They remain a studio either blissfully unaware of their unorthodox market tactics or completely at ease knowing they have built (and sustained) a voracious, defensive fan base. Splatoon’s pop-up, user-made messages in Inkopolis are bizarrely safeguarding of their chosen corporate monolith. “Our game is better than this one” and “Nintendo is awesome” are their sole projections to the outside world, their whole exterior identity. This community is safe but not personable unless you made them a video game. And you work for Nintendo.

Likability in Droves

There are reasons for the support. Splatoon is doing everything it can to be outwardly likable. Splatoon even connects to Nintendo’s unnecessarily hot Amiibo figures – begrudgingly to unlock chunks of content – and layers itself with a negligible (tutorial-esque) solo mode against alien Octarians. Odd, since all of Splatoon feels alien. This scattered side mode fails to capture the entrancing fluidity of multiplayer or the majesty of Nintendo’s lavish Mushroom Kingdom world building.

It’s throw-away material for if, or when really, Nintendo unplugs their support. Some of Splatoon can then still exist. For the very Nintendo approach elsewhere, Splatoon’s hooks into online infrastructure forcibly removes the game from any future examinations.

Local one-on-one ink combat is hardly a replacement for the activeness of four-on-four. No one will avidly collect or cherish Splatoon in 10 or so years like they do Super Nintendo’s Super Mario World. There are now caps and limits to how long Nintendo games last. Nostalgia will remain but it’s not the same.

Maybe a lifespan is what Splatoon needs. It is a test, a mere inventive nudging into untapped markets to see how a fanbase reacts rather than all-in production. Cute, clever, even conceited. Ultimately, Splatoon won’t be with us forever; so, thankfully, it’s easy to enjoy in the now.

Published: Jun 3, 2015 07:01 am