Imagine you’re going about daily life, minding your own business. Suddenly, you receive a letter from a friend named Henry Allen you knew long ago, back when you lived in an orphanage.

It’s a strange letter, full of regret for something Henry is about to do. He’s asking you to move to his city, take up his business, and keep watch over his wife, Juliet, and mother, Dana. The city is dangerous, he says, full of things you can’t understand, but you must pay attention to the shadows because they’re important.

It goes on like this, becoming more fevered and frantic, until it finally stops.

You then learn Henry committed suicide, though there’s some doubt over whether he hung himself — or was murdered.

So, what do you do with this information? How do you live, and do you carry out Henry’s last requests?

That’s exactly what AI Pixel’s A Place for the Unwilling tasks you with figuring out on a daily basis in the 21 days you have to live until the city is swallowed by darkness.

Endless Variety

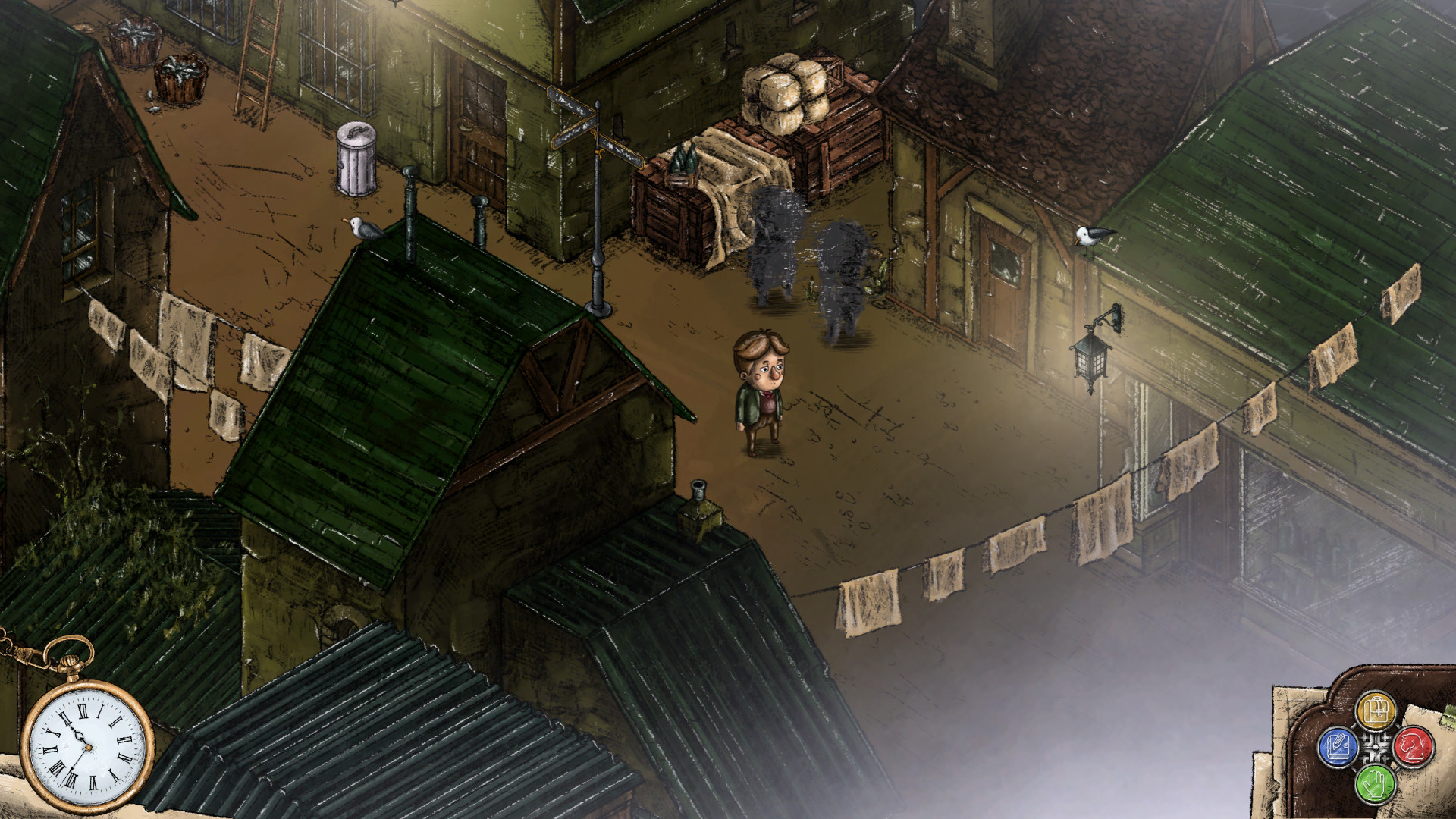

Every choice you make counts in the game, from how you sign your letters to which shops you frequent and whether you take sides in the city’s growing class war. You won’t see everything there is to see in one playthrough, especially because the game uses a Harvest Moon-style clock, where one real-world second equals one in-game minute. Time flies.

The story starts with you establishing some basics about your character — name, gender, preferred pronouns — and choosing how you want to save the game. This is actually more important than it initially seems, depending on how you want to approach gameplay.

The first is saving at the beginning of each day, and the second is saving when you want to exit the game. If you want to play the game completely blind, the second option is best because it’s not as easy to see how one option turns out, then reset to pursue another.

Those who prefer seeing all the various permutations might find it better to save at the beginning of a day, play through one way, then start that day again and do it differently. Prepare for a lot of restarting if you want to do this, though.

The Right Choice

The game’s charm likes in making spur of the moment decisions and forging your path as you move, or sometimes blunder, along.

You’re presented with a handful of bigger choices early on. The first is whether you want to take up Henry’s buying and selling business or focus on uncovering the truth behind his death. Of course, you can do both, but your response when people asks what you’re in the city for — business or the truth — affects how they view you.

Admittedly, the business side of things isn’t too exciting. The city has a handful of shops, each offering the same items — toys, combustible goods (of course…?), food, drinks, and the like. Prices change daily, and the idea is to buy cheap from one shop, then sell at a profit to another.

Yeah, you probably spotted the logic gap there. Most good merchants don’t saunter down the street to sell some books they bought five minutes ago from Ms. A to Mr. B and expect everyone to be happy about it.

You’ll still need to do some trading from time to time if you want money, and you will want money. It’s used for fast traveling and buying non-tradeable goods, not to mention some quests require a healthy sum of money to complete. It’s just more of a necessity than an enjoyable feature.

Whatever you choose to do, you get some suggested tasks on most days to help guide you along. None of them are mandatory, and thanks to the city’s size and your snail-like movement pace, it’s impossible to do them all. However, the point is to get out and talk to people.

It’s only a few people, at first. Those “shadows” Henry mentioned are all around in the city, people you don’t know who don’t know you. They’re too busy to chat with a complete stranger the newspaper says has questionable acquaintances.

Depending on tasks you complete and choices you make, some of these figures shed their dark cloak, gaining faces and names — yet not necessarily becoming friends, again depending on your choices. You do get to learn more about them if you choose to, which can eventually unlock different tasks or story paths.

The Company You Keep

In fact, it’s tough to say if you make any real friends during your time in the city.

Dana Allen, Henry’s mother, throws a welcome-and-mourning party when you arrive and seems to be on your side, but she has a terrible reputation among people of her class. And that migraine medicine she gave you — why does your head start hurting worse when you take it?

Then there’s Juliet, the grieving widow. She won’t speak at first, then she tries ascertaining your motives, before getting you to join her side in the “war” against Dana, or you can choose to be neutral. Henry chimes in through dreams from time to time to clarify what’s going on, but you always wonder whether you made the right choice.

Not every character forces huge choices on you, but it can’t be emphasized enough. Every. Decision. Counts. Whether it’s how you sign a letter, what tone you take during certain conversations, who you help out, or whether you interrupt someone or let them continue, everything matters.

Helping the poor improves your friendship with Ms. Peyton the shopkeeper and sets you apart from the callous wealthy citizens, but spending the mayor’s surplus on charity doesn’t sit well with him — especially if you listen in on his phone conversations before making your presence known.

Telling the posh newspaper hawker you feel sympathy for the poor runs the risk of giving you a bad reputation on the nicer side of the tracks, but repeatedly helping Myles forms a relationship with the city’s revolutionary downtrodden. The opposite can be true as well.

All of this affects how the story progresses, which tasks are available, and how you can relate to other people. The endless variety and multiple opportunities keep the game engaging throughout, partly because you end up feeling so invested in this strange world with its kind but dangerous inhabitants.

Coming Alive

It’s not all slice-of-life, though. A distinct plot begins to unfold after a few days, involving the supernatural and an odd cult, with Juliet and Dana taking opposing sides.

Because you don’t get a whiff of this until you’ve established your bearings in a world that seems grounded in reality, the supernatural elements initially come off as out of place. However, that soon just becomes part of the city’s dark quirkiness.

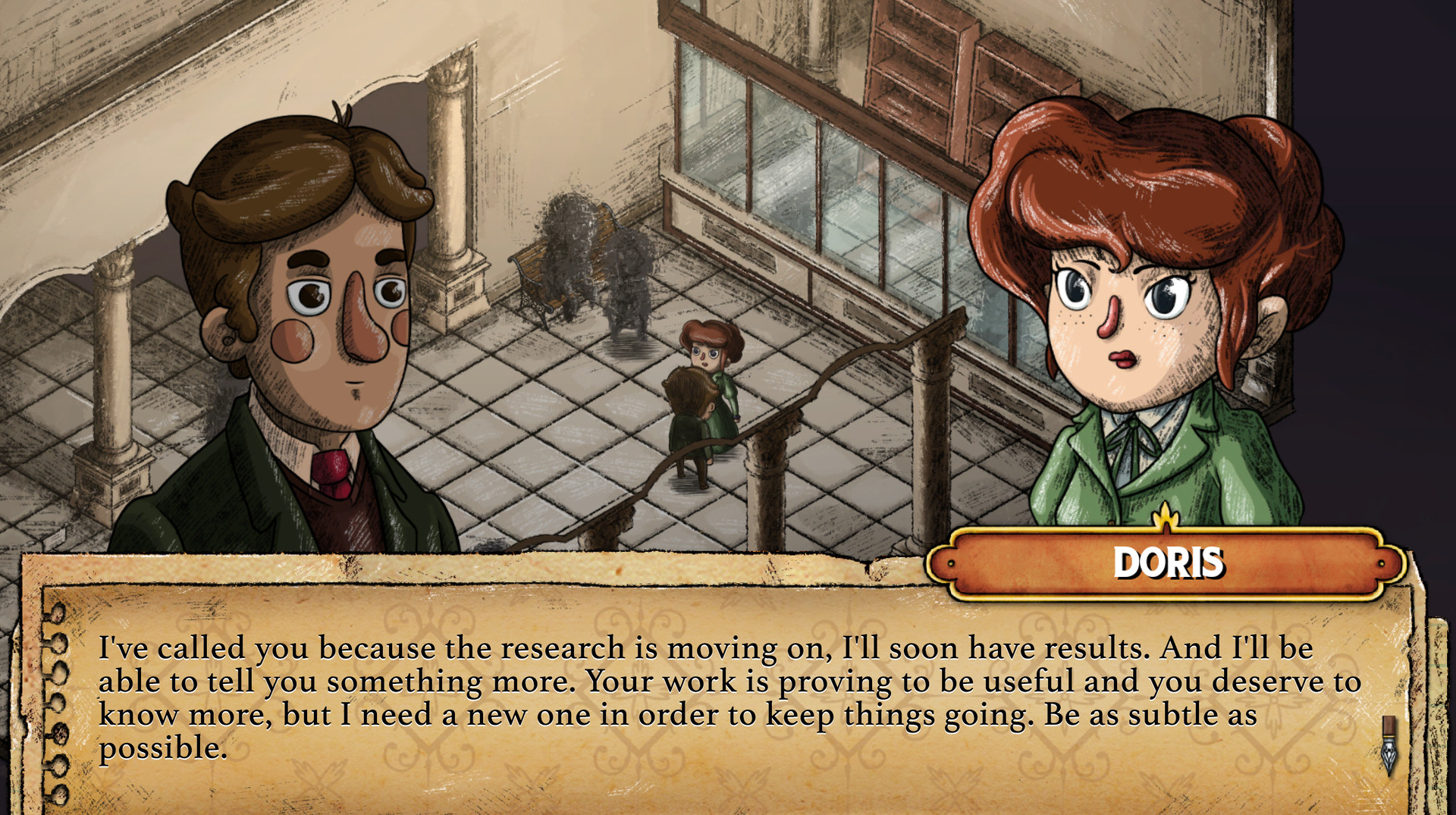

The attention to detail isn’t limited to just character interactions and branching paths. The unnamed city (*cough cough* London *cough cough*) is rendered in a soft, hand-drawn style complementing the historical setting, and the character portraits, though exaggerated, convey tons of personality just with their few static images.

Dialogue isn’t voiced, but there’s a special touch added that arguably lends more character than even voice would. Dialogue is presented as if written in pen on parchment. The text scroll flow fits perfectly with spoken dialogue, and its cadence changes depending on the context.

Plus, each character has their own style and sound effect. It’s a minor touch absolutely brimming with personality. There’s the main character’s measured, steady pace and the flighty Mrs. Clinton’s scribbled-sounding scrawl. Juliet’s is looping and complex, while the corrupt policeman August’s written speech is clumsy and heavy-handed.

False Stepping

Unfortunately, this close attention doesn’t extend to everything.

The bookshop owner, Lucas Weston, says he speaks in singsong, but his speech style doesn’t change to match that. The music, rich and always area appropriate when it does play, cuts out seemingly at random.

One night, when you “accidentally” drink too much with the local seadog, you fall flat on your face (after some rather amusing dialogue changes). The sailor remarks about you being out for so long, but then you’re on your feet again, with no time having passed.

These are little things to be sure, but they begin to add up and occur more frequently after the first few days.

There are a few other minor quibbles.

Yes, the game is about time management, but making character movement so slow where even casual passerby move faster seems like an artificial way to keep you from accomplishing multiple tasks. For instance, going to the lighthouse takes almost 3/4 of the day until you can fast travel there.

An almost completely blank map doesn’t help matters. Naturally, a newcomer isn’t going to know where things are, but you are given a map after all. Maps usually have places marked on them, and even strangers in the street can point you in the right direction. Not here.

Then there’s the grammar. The worst thing about it isn’t syntax or anything like that. It’s the fact that the errors are completely avoidable. Missing words, repeated words, words you phrases you meant to delete because you thought of something better — all of these make an appearance, with increasing regularity as the game progresses.

This is something an editing pass would catch, and it’s surprising to find so many problems in a final build, especially in a game built around writing.

There is one specific issue: the F-bomb. A Place for the Unwilling hurls it at you pretty often, and it doesn’t fit the context.

Now, your humble writer knows the Victorians weren’t prim and proper, whatever the common belief might say to the contrary. Underneath that polite veneer, the Victorian era was as raunchy as they come. That goes double for the Fin de Siecle (French for “end of the century,” roughly the 1880s-1890s). This was a time of glorious debauchery, by 1800s’ standards, full of experimentation, loose living — in other words, the Victorian equivalent of the 1960s.

And that’s the point. The big F was primarily used in its more literal context, not as the descriptive stand-in so common in modern usage.

That’s how it’s used by folks in not-London, though. “Stop f***ing staring”, says the policeman. Or from a member of the lower classes, you get the always popular “F***, stop f***ing staring ar*eh**e, jesus” (with a lower case “j”).

Some well-chosen four-letter words are fine and can add to a given character or create a certain mood. Using them just to use them, especially when they don’t even fit, takes you out of the game and lets the rest of the usually well-considered writing down, writing that actually conveys meaning.

—

The Verdict

Pros

- Intriguing and compelling story and characters

- Highly engaging branching choice system

- Gorgeous aesthetic style

Cons

- Needs a final polish

- Some design issues and questionable writing

- Lack of puzzles and other activities might turn some away

A Place for the Unwilling definitely needs some extra tune-ups, and the early days might prove frustrating for some, before a clear idea of the city’s layout sets in. F*** being chucked at you left and right gets really old really fast, and the other slip-ups are disappointing in an otherwise carefully conceived game.

However, its stronger points help push past these issues. There’s a mystery to solve and a world to save — or not. Here you find a large cast of bizarre and potentially sinister characters with dubious motives. Whether they’re trustworthy, you never know, but you push on and make nice to hopefully uncover the truth before it’s too late.

Whether you’re the poor person’s friend or a jerk in a stuffed shirt, A Place for the Unwilling offers a deep and compelling story that’s never going to be completely the same, no matter how often you play it.

[Note: A Steam key of A Place for the Unwilling was provided by AIPixel for this review.]

Published: Jul 24, 2019 02:18 pm