Nintendo might not have been a big player in the gaming market prior to the 1980s, but there's no denying the Big N's left its mark on the industry ever since.

Though lambasted for seemingly inscrutable decisions or appearing out of touch with the modern industry and consumer needs, Nintendo and its innovations were also partly responsible for shaping how the modern gaming industry developed in some key ways.

Not all of its innovations were huge successes of course — hello, Wii U — while some built off the success of previous products and took them to new heights or paved the way for vital parts of modern console construction.

Whether it's something as foundational as a new interface method or as dramatic as rescuing the industry from sliding into the abyss created by shovelware, Nintendo earned its place as one of the foremost companies in the gaming industry. Here are five of the biggest innovations Nintendo's cranked out over the years.

The D-pad

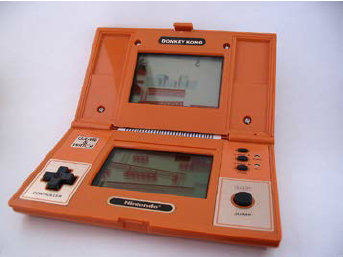

This one should be fairly obvious why it’s innovative and worth discussing. Until Gunpei Yokoi decided the Game & Watch version of arcade classic Donkey Kong would work better with a D-pad, games were played either with a joystick or mouse-and-keyboard combination.

That’s fine under the right circumstances. But plunking an arcade-style joystick in the middle of a small gamepad really just doesn’t work that well, the Commodore 64 had the keyboard covered already, to middling effect, and Coleco’s multi-button phonepad was perfect for octopi only.

EIther way, the goal at this point was differentiating Nintendo’s products from the failed Atari, especially in the West, and joysticks would not be the way to achieve that. So, the humble D-Pad was born and has sort of stayed around ever since after it became a feature of the Famicom/NES gamepad.

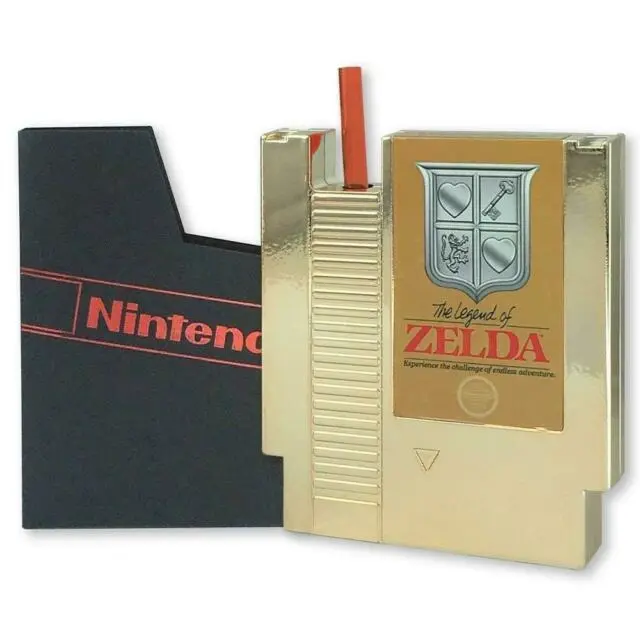

And it might be more innovative than you’d initially think. Imagine controlling Link in the first The Legend of Zelda with just a joystick. Along with generally just being clunky, it’d get pretty tiresome after a while. That doesn’t even take into account issues of accuracy, like those jumps in Super Mario Bros. that require absolute precision — something you definitely don’t get with a joystick.

That’s probably why scholar Alan Richard da Luz argued, at the Human-Computer Interaction conference in 2014, game interfaces like the D-pad evolve over time as complements to the gameplay and narrative experience. A D-pad gives far more tactile response than a joystick, helped along by that general feeling of connection between the direction buttons (conspicuously absent in the base Switch’s four arrows).

Just like that, literally with the press of some buttons, you’re taken out of the gimmicky arcade cabinet experience and pushed into something much more immersive, where you feel and see your actions on that little pad causing direct effects in the game world. When that coincides with deeper and more varied experiences like the NES and Game Boy offered, then you get a winning combination of convenience and immersion..

And then Nintendo takes it away again with the Switch in a move we can only look at and laugh over.

The NES, Gaming's Salvation

What makes the humble Nintendo Entertainment System innovative? You might ask. After all, it wasn’t the first console. Atari had that covered. What Atari didn’t have, though, was quality — not leading up to the 1983 video game crash, at least.

The flood of what today we’d call shovelware meant both that the games industry was very close indeed to collapsing on itself, as consumers balked against the rising tide of garbage games and what basically amounted to advertising material. That's something we still see today, but not at the percentage the industry saw pre-crash.

Enter the NES.

After a failed partnership with Atari and some big redesigns attempting to distinguish it from the Famicom, Nintendo finally released the system in the West. There were a few things that made the NES different from its predecessors and essentially saved the video game industry, but the biggest was the software.

It’s hard to realize it now, but NES games completely revolutionary, unlike anything that came before. Defender kickstarted the sidescroller and Gradius took it a bit further, but Super Mario Bros. refined it by combining platforming adventure with a huge array of obstacles, and a human character instead of the tired spaceship everyone had grown used to.

The Legend of Zelda wasn’t the first adventure game either, but its structure, coherence, and design were all vastly improved from the weird blip that was Atari’s Adventure. Of course, the NES was home to some crap games too, but Nintendo’s licensing policies — where the good ol’ seal of quality came from — prevented the NES from going the same route as Atari and ensured the games industry’s survival.

Ironically, Nintendo later reversed that policy with WiiWare and now the Switch eShop, so we get some titles with lightly questionable quality after all.

Though some credit things like R.O.B. and the NES’s overall style with keeping it from self-destructing, it’s hard to justify those claims. The 1986 survey that tried to find out how many NES owners bought it because of the R.O.B. toy and style only surveyed 200 people.

By the end of the following year, Family Computing Magazine pointed to the likes of Super Mario Bros. and Zelda as reasons to own the NES, saying R.O.B. was cute, but basically pointless. Sorry buddy.

Handheld Gaming

Handheld gaming started long before Gunpei Yokoi’s Game Boy system launched. The first handheld video games can be traced back back to Milton Bradley’s Microvision, that clunky retro gem of a system with the tiny screen. It was innovative on its own and launched with a variety of titles, but it was also highly impractical. The screen broke too easily, and it was so tiny.

Around the same time, Yokoi headed development of the old handheld Game & Watch devices for Nintendo, most of which featured the silhouette man many now know thanks to Smash Bros..

Others were miniaturized versions of arcade classics, though, like Mario Bros. (the un-super variety) and the Donkey Kong line of games (before the Kongs established their own country).

That fact itself is remarkable in an industry built around games only being played on massive computers, arcade cabinets you couldn’t take home, or units you could take home like Atari that tied you to a TV.

These were mostly short games and very arcade-like in scope and structure, or just copies of what you could get elsewhere, plus even Microvision was able to swap out multiple (expensive) cartridges on one system — something Game & Watch couldn’t do.

That’s why the Game Boy itself was an even bigger innovation. You had the bigger, for its time, screen, plus a decent launch library with tons more games to follow, games that carved their own path completely separate from their console counterparts.

From Metroid II sending Samus into the depths of the bleepy monochrome Metroid home planet to Link exploring the island of his dreams in Link’s Awakening, the Game Boy offered a completely new handheld experience — so long as you had the batteries and just the right light for it.

From there, Nintendo has continued innovating in handheld gaming, improving systems, offering experiences that are sometimes arguably better than console games, and now, of course, coming close to making handheld gaming itself a thing of the past by blurring the console boundaries.

Blurring Console Boundaries

That blurring actually began long, long before the Switch. One could reasonably say it started with the handheld Game & Watch, where Nintendo tried replicating the arcade experience in handheld form, and the Game Boy carved a separate niche for handheld games.

Then came the NES era, when Nintendo Japan released the Wide Boy adapter. It unfortunately never came West.

In the SNES era, though, Nintendo released the Super Game Boy peripheral, which did exactly what the name says: it let you play Game Boy games, and some Game Boy Color games, on your Super Nintendo.

That meant, well, that you could play Game Boy games on your TV. They were blown up to whatever size your screen was, and you could choose several different color palettes and background frames to make the space between the game border and the edge of your screen more interesting.

Fancy it might not have been — the JP-only Super Game Boy 2 had more bells and whistles technically — but looking back, you can see it was a step towards the philosophy that led to the Switch.

The Nintendo 64’s peripheral was for dev-use only, so then we skip ahead to the Game Boy Player. It’s basically a gussied-up version of the Super Game Boy that lets you play Game Boy Advance games on your big screen, and then the console divide widened again after the DS and Wii came on the scene.

It’s not surprising. Both offered their own unique gimmicks that increased sales and solidified Nintendo’s two main audience segments. Why experiment from there and risk alienating either segment when both are so happy to give you money?

Apparently, it’s because Nintendo just couldn’t stay away from the idea of blending console and handheld experiences. We all know the Wii U wasn’t quite what it could have been, thanks to some iffy marketing, lack of third-party support, and, frankly, somewhat confusing main feature.

Still, it was basically the Switch 0.5, offering players the chance to play their console-quality games on a portable device without losing much in quality except some pixels.

That concept blew up enormously in 2017 when the Switch launched, offering games like The Witcher 3, Doom, and Breath of the Wild on a portable device.

With the 3DS basically on Palpatine-levels of life support at this point and the VIta well and truly buried, it’s safe to say Nintendo’s first innovations with the Wide Boy and Super Game Boy paid off big time in creating something completely unprecedented in the games industry.

It’s even more interesting considering Nintendo basically created the handheld gaming market to begin with. Nintendo giveth handheld gaming and Nintendo sort of taketh it away, I guess.

Save Batteries

I could just leave the heading here, and that would suffice. Really, save batteries were probably the best things for gaming alongside the NES, and we still benefit from their beneficence today.

“Beneficence” isn’t just used there for snazzy word choice either, as most parents would probably agree, because there is a kind of obligation developers have to make their games actually playable long-term without completely imploding.

Prior to The Legend of Zelda, almost every game had no way of letting you continue your fun. Some arcade cabinets had a kind of suspend feature that let you pop more coins in for additional fuel or whatever to continue going, but there wasn’t any real way to actually back up your progress.

The lines blur a bit as far as who actually innovated with the idea of battery-powered save files. Pop and Chips, a 1985 game on the Super Cassette Vision utilized a literal battery save, where the feature used two AA batteries to power the save file.

Why Pop and Chips used this feature is a little less clear. It’s essentially the same kind of game as Bubble Bobble, not exactly requiring suspended or saved data for progression purposes. However, Nintendo’s Family Basic programming tool for Famicom games used a similar AA battery-powered feature a year prior to Pop and Chips, though of course, a programming tool and an actual game are two different things.

Regardless, fast forward to 1987’s release of The Legend of Zelda, and Nintendo offers something in that cartridge that would stick around for a long time: a CR2032 battery that lets you record your progress. Games like Zelda would have been nigh-on impossible without this feature, though Nintendo didn’t adopt it full force for a while yet.

Many — too many — SNES-era games relied on password systems that half the time never worked, much to the chagrin of players and parents the world over. However, as the era progressed and transitioned into the next generation of gaming, the save battery sparked changes. Some games used the little CR2032, while others such as Neo-Geo and Sony looked to memory cards for saving salvation.

The Xbox was the first system to use built in memory, and that pretty much takes us where we are today, with systems packing various degrees of internal storage and almost completely removing the need for any kind of external backup — except Nintendo, ironically. The Switch absolutely needs an SD card for storage thanks to its teeny 32GB internal storage system.

Still, the save battery led to these developments and made possible all manner of gaming experiences we never would have had otherwise.

Motion Control

Motion control has technically been around much longer than Nintendo. Arcade cabinets used variations of it, from the boxing glove of Heavyweight Champ to those motion-controlled vehicle games in movie theater lobbies that let us take control of a jet ski or X-Wing. Nintendo and Sega both tried early forms of motion control with home consoles, with the NES' Light Zapper and Sega's Activator, neither of which was really all that successful.

From there, motion control became a gimmick of sorts. Nintendo spin-offs like Kirby Tilt 'N Tumble and Yoshi Topsy Turvy, along with Dreamcast classics Sega Bass Fishing and Samba De Amigo used variations of motion control. But it's telling that these were limited to spin-offs and experimental games. The market wasn't ready for motion control, and neither were developers.

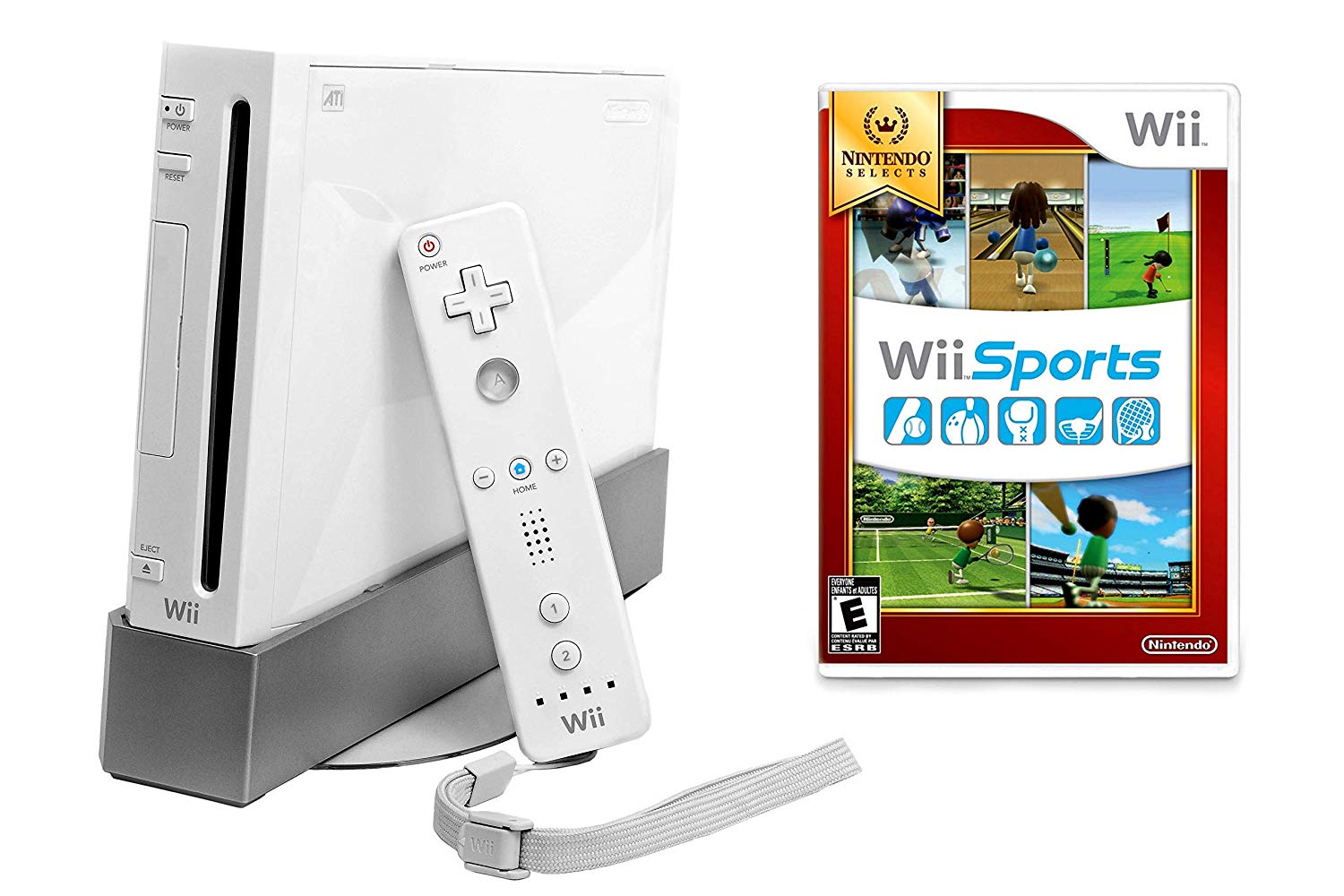

Fast forward to 2005. Nintendo unveils the codename for its newest system, the Nintendo Revolution that would later be dubbed the Wii. Conceived as a way to carve a new place for Nintendo in a market dominated by expensive, powerful consoles, the Revolution was exactly what it sounded like, a huge shake-up for the games industry all thanks to the "revolutionary" input device that relied on motion control.

How the Wii's motion control was revolutionary depends on perspective. It certainly re-invigorated gaming, drawing in hordes of people who'd never before touched a game in their lives while at the same time offering new ways to experience gaming for long-time gamers.

The Wii's brand of motion control inspired Sony and Microsoft versions as well, and though it can't be said for certain, the widespread acceptance of motion control could have had a hand in pushing VR gaming forward as well.

Admittedly, most of these motion control games devolved into gimmicks themselves, with precious few examples that really made good use of motion control. Its real legacy is in bringing people together and pushing gaming further into the mainstream.

The DS and Touch Control

What do you do when you own the handheld gaming market and have brought handheld systems to new heights of efficiency and convenience? You create a chunky device from a 1980s dream of the future, try and market it with would-be sexy touching games and ads, then say screw it, dump a ton of games on it, and sell it to millions upon millions (upon millions) of people.

In case you didn't know, that's what Nintendo did with the original DS.

The DS' big draw was, of course, the revolutionary touch screen on the system's lower half. It threw open the doors of creative possibility and led to what was easily one of the best libraries of handheld gaming — and Nintendo's biggest marketing successes.

The reason was simple. Touch screen use could be as complicated as drawing your own map to get around in a labyrinth or just streamlining menus for RPGs like Pokemon. It pre-dated the Wii U gamepad as the ideal form of inventory management and even offered some truly fun — and sometimes truly hideous — methods of making characters move around.

For the first time since the D-pad, the simple act of moving characters was once again exciting and immersive, like the Wii, capable of re-igniting old gaming passions and sparking new ones.

Sony and Microsoft didn't jump on the touch screen bandwagon quite the same as they had the motion control wagon, just because it's harder to make as an add-on like Kinect, let alone to make it work right (look at the Vita's rear touch screen, for example).

Nintendo itself was iffy with its touch screen support after a while, especially moving into the Wii U era when it basically was just inventory management. Now with the Switch, we see a touch screen that gets very little use indeed. And that's a shame given its potential for creative game design.

---

These are just a few of the major ways Nintendo innovated over the years. There are countless others, and not just from Nintendo, so tell us your favorite gaming innovation in the comments below!

Published: Dec 20, 2019 03:48 pm