Spoilers: The games below are discussed in great detail, though all spoilers are confined to each game's section. Skip any sections for games you haven't played. Also, go play those games. Seriously.

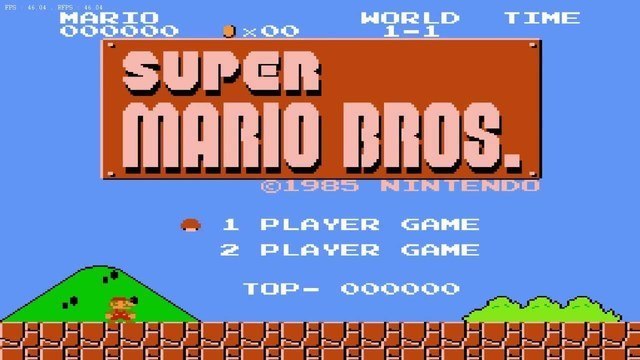

We all know it to be true: Mario is, without question, the single most influential character in videogame history. From the day our red-capped hero first hopped onto our screens, Mario has been an irrevocable icon not only in the gaming industry, but in all mainstream media worldwide.

A masterclass game even today, one which all at once saved the industry from the videogame crash of 1983 and paved the way for games of its generation and the generations to come, it is safe to say that Super Mario Bros. will be a game remembered and revered for centuries.

There are few who understand this game's importance better than today's game developers, who have been consistently recycling and reiterating on ideas first introduced by Nintendo's legendary title in ways both big and small. However, as games evolve, complexity grows, and game design strays further and further from the foundations first established by the likes of the world's favorite Italian plumber.

Enter the indie devs. In the latter half of the 2000s, the gaming industry saw a rise in independently developed videogames, due mostly to the new accessibility of digital distribution. Many of the developers behind these games, having no ties to big-name publishers, had a certain artistic drive behind their ambitions. Although still seeking compensation for their work, these developers were equally concerned with their artistic integrity as they were with their financial success, if not more so.

If [Super Meat Boy] makes $20,000, that would be enough to make the next game... Even though it's a game that people are supposed to buy, it's not a game that I made for people; I made it for myself. Ed [McMillen] and I made it as a reflection of ourselves.

-Tommy Refenes, Super Meat Boy developer

Though many of these new artists hope to innovate and venture into the unknown, some indie developers have taken it upon themselves to pay tribute to the great games of past generations. And of course, no game has been celebrated in this form more than Super Mario Bros.

These indie games take from Super Mario Bros. and other 2D classics in ways best suited to each individual game. The creators of Fez chose to use platforming as a simple means to traverse the game world in a tranquil and engaging collectathon, while Team Meat took an approach more focused on the timing and precision of Meat Boy's platforming skills.

However, while all of these developers set out to create something unique, there is one theme under which many of them stand united; a paradigmatic element that calls directly back to Mario, making these games a masterful collection of odes to the Italian plumber.

In each of these games, you must save the princess, and she's always in another castle.

Super Meat Boy

The developers behind this legendary XBLA title were anything but subtle in portraying their influences. Many, if not all of the cutscenes in Super Meat Boy feature shot-for-shot parodies of iconic moments in games like Mega Man, Castlevania, and even Pokémon.

But the greatest ode to any of the classics is saved for Mario, taking form in not another clever cutscene, but in the moment-to-moment gameplay. Though 2D platformers were already on the rise, no contemporary of Super Meat Boy offered such hyper-precise controls, excellent map design, or smoothness in progression of mechanics. Of all the games mentioned in this list, Super Meat Boy stands as the truest dedication to Mario in both gameplay and presentation.

It isn't hard to see the parallels between Team Meat's super hardcore platformer and the Nintendo title that started it all. Indeed, even the name "Super Meat Boy" sports the same initials as Super Mario Bros. From the game's opening cinematic to the final blow dealt to the evil Dr. Fetus, references to Mario are littered throughout Meat Boy's arduous journey to saving Bandage Girl. In fact, this journey itself is a parody of Super Mario Bros.

Most gamers can easily recognize the Mario-Peach-Bowser paradigm in Super Meat Boy. However, Meat Boy's story has more endearing qualities amidst tongue-in-cheek humor. Bandage Girl is not royalty; she is essentially an equal to Meat Boy (besides being a semi-typical damsel in distress). The imagery of Bandage Girl clearly suggests that she is a real necessity in Meat Boy's life.

Most gamers can easily recognize the Mario-Peach-Bowser paradigm in Super Meat Boy. However, Meat Boy's story has more endearing qualities amidst tongue-in-cheek humor. Bandage Girl is not royalty; she is essentially an equal to Meat Boy (besides being a semi-typical damsel in distress). The imagery of Bandage Girl clearly suggests that she is a real necessity in Meat Boy's life.

Conversely, it may have become more clear to us several game generations later that Mario is infatuated, if not in love with the princess. But it wasn't so clear in the initial game. For all we know, Mario is doing no more than his civic duty to the Mushroom Kingdom by taking up arms to rescue the princess (or something far more sinister, as many conspiracy theorists believe). In Super Meat Boy's case, it is very clear from the start that Meat Boy is on a quest of the heart.

Unfortunately, this proves to be one of the most relentlessly unforgiving quests of all gaming history. Throughout the game, Meat Boy is beaten, squashed, sliced, and otherwise inhumanly slaughtered over and over again. The game makes Meat Boy's sufferings gruesomely apparent with a kill-cam compilation of every failed attempt playing upon finishing each level.

What makes this all the more painful is that even when he does reach Bandage Girl at the end of each level, she is once again snatched away by Dr. Fetus. No matter what our efforts, no matter how great our triumphs, the developers here constantly remind us of the inescapable truth that our princess (Bandage Girl) is always in another castle.

Shovel Knight

More of a tribute to all classics of the "bit" era of gaming rather than focusing on one title (though one could argue Mega Man is favored), Yacht Club Games took the best gameplay bits (I'm gross) from the greatest of these games and applied them to Shovel Knight with elegance and grace.

Its gameplay, bosses, and level designs are inspired by Mega Man. Its charming world map, with its roving parts, limited non-linearity, and inconveniently sealed-off segments will be recognizable to anyone who has played Mario 3.

Its combat contains a significant dash of Duck Tales. Its hub towns, inventory and money systems — as well as its cast of NPCs to interact with — represent a hybrid between Zelda II and Faxanadu, while its sub-weapon system is an ode to Castlevania and Ninja Gaiden. The real beauty of Shovel Knight isn't that it's a clearly worded love letter to the storied NES era; it's that it drew inspiration from nothing but great NES games.

- Shovel Knight Review by Colin Moriarty

Though the game combines mechanics from various classic NES titles while featuring a primary format derivative of Mega Man, the driving force behind Shovel Knight's endeavors is, once again, saving the princess — or, in this case, Shield Knight. Each night, our hero becomes increasingly consumed by his quest — his dreams encumbering him with guilt over what the player assumes is her untimely demise.

However, we later find out that Shield Knight is not deceased, but corrupted by the power of the Enchantress, and that Shovel Knight has been pursuing the Knights of No Quarter to rescue his fellow Knight. Therefore, he is in a way fighting to rescue the "princess."

And rescue her he does... for a moment. Immediately after liberating Shield Knight, both she and Shovel Knight are faced with an even greater obstacle; one which can only be overcome by working together.

This somewhat trumps the Mario/Princess paradigm, seeing as Shovel Knight not only depends on Shield Knight's assistance (and vice versa), but is also saved by this "princess" when she sacrifices herself to defeat the Enchantress and give Shovel Knight a chance to flee. In this light, Shovel Knight serves as a more progressive take on the Mario/Princess paradigm, one which favors a more gender-neutral interpretation (also slightly reminiscent of the ending sequence to Zelda: Ocarina of Time).

As far as the "princess is in another castle" requisite goes... call it a stretch, but I feel the Shield Knight sacrifice sequence could serve as a somewhat extreme reinterpretation of this model. Shovel Knight fought the entire No Quarter (twice), freed Shield Knight from her possession, then defeated the Enchantress, only to lose the one he cared for most all over again.

Whatever woeful grief you went through when Toad first gave you his unceremonious apology, I'd say Shovel Knight's got you beat.

LIMBO

Playdead's premiere title presents a much darker and more indeterminate interpretation of the model in question. While Super Meat Boy and Shovel Knight featured endearing parodies and humorous references to classic 2D games, LIMBO draws parallels with only a few (or perhaps one) of these games with a grim subtlety. The two previous examples certainly featured simplistic stories, but LIMBO's plot sets the standard.

Uncertain of his sister's fate, a boy enters the unknown.

True to its word, any further details of this game remain unascertained. Such ambiguity always leads to speculation and interpretation, and with LIMBO's popularity, many fan theories about the game's meaning have been circulating the internet since its release.

Some adopt a more literal school of thought, believing the Boy and his Sister have entered a post-mortem reality where they must atone for their sins. Others believe the gameworld represents the Boy's greatest fears manifested to extremes (e.g. giant freakin' spiders), and that he must face them head-on in order to save his sister.

One of the more morbid theories identifies the Boy as the antagonist, referring to the actions of the other children in LIMBO and the game's title screen as evidence.

Though each of these holds validity in its own respect, one critical element unites each theory behind this game: the sister. No matter where the boy is or how he got there, his quest remains unequivocal.

Similarly, in Super Mario Bros, we are tasked with saving the princess, though only a select few players knew the reasoning at the time. I don't know about you, but 4-year-old me had no love for reading, thus resulting in a swift trip to the trash for Mario's instruction booklet, along with the little detail given on why I should consider continuously venturing from left-screen towards the ever-expanding right-screen. LIMBO calls on this now inherent instinct in order to reward us with a glimpse of our goal towards the end of the game, only to be denied.

In Chapter 29, the Boy seemingly finds his way out of the industrial labyrinth of gears and saw blades to find himself back in the wilderness. Venturing rightward, the Boy finds his sister, her back turned to him, seemingly in prayer or at play. He eagerly runs to her, only to be turned around by another sneaky brain worm, bringing him back to the nameless factory he had just escaped. When the Boy finally makes his way back to the exit... it has disappeared. No wilderness, no exit, no sister. His princess is in another castle.

Skip to 0:20

Braid

Jonathan Blow's critically acclaimed platformer takes Super Mario Bros' format and flips it on its head, spins it around, then flips it right-side up again and swears it was all just a bad dream. Much like Super Meat Boy, the Mario/princess paradigm in Braid is made evident immediately upon entering the first world.

However, as the player progresses through the game, the ambiguity of Tim's quest becomes increasingly peculiar and even disturbing. The first oddity lies in the missing World 1; the first world available to the player is labeled World 2, giving us reason to believe that we are being told Tim's story out of order. This is the first flaw in the game's narrative — a flaw intentionally created by a manipulated perspective.

The second oddity is presented by Toad's apparent replacement. With each level's end, Tim is greeted by a dinosaur who tells him that the princess is in another castle. However, this message is delivered with increasing confusion. By the final available level, the dinosaur admits that he has never actually met the princess and even asks Tim if he's certain of her reality.

This solidifies any speculative doubts the player might have developed for Tim's perspective. The game started with a very concrete fact: the princess had been snatched by a horrible and evil monster. Now, Tim's credibility has been nearly obliterated. That is until we enter the last level of World 1.

Here, we finally are given a second perspective on our story, courtesy of none other than the princess. Upon entering the final level (prior to the epilogue), we see a burly knight climbing down a rope, clutching the princess. As they fall, the princess seems to escape the knight's clutches and calls for help as the knight beckons her back down, growling like the horrible, evil beast he is.

Tim and the princess then run away from impending doom, the princess throwing switches to aid Tim as they flee. Finally, they both are about to reach each other when — everything stops. The game hints at reversing time. As the player does so, we see the events of moments ago transpire in retrograde.

Only now it tells a very different story. The switches thrown by the princess seem to be used against Tim, keeping him away. Dropped chandeliers, closing barricades — all seem to now be working against our hero. Finally, the princess reaches the knight, still beckoning her to come down. Obedient to the retrogression, the princess obliges the knight, and together, the two climb away from the evil Tim, both looking far happier than we remember. This, of course, is the princess's side of the story.

Is the knight the monster? Is Tim? Is the princess even real? Does the entire game serve as a symbolic reminder of the Manhattan Project? Gamers and critics are still pondering the meaning of this game today and will most likely continue to do so for a very long time.

But for all the ambiguity and mystery surrounding this game, there is one certainty: no doubt, Braid will stand as a great allegorical milestone in gaming history.

Heroes (In Conclusion)

In its beginnings as a videogame company, Nintendo offered the world several masterclass games, all featuring a story that had been told hundreds of thousands of times before: the male hero must save the damsel in distress. As art forms have evolved — theater, music, literature, opera, poetry — each has gone through stages of primitivism similar to Mario's borderline sexist plotline, eventually revisiting these ideas from newer, more progressive perspectives.

In its beginnings as a videogame company, Nintendo offered the world several masterclass games, all featuring a story that had been told hundreds of thousands of times before: the male hero must save the damsel in distress. As art forms have evolved — theater, music, literature, opera, poetry — each has gone through stages of primitivism similar to Mario's borderline sexist plotline, eventually revisiting these ideas from newer, more progressive perspectives.

Braid is not just an ode to the world's favorite Italian plumber; it is a turning point in the medium, one which takes the two-dimensional format of the Super Mario Bros. plot and adds a new dimension through multiple perspectives, thus making the player question the narrator, the game, and sometimes themselves.

In the year 1804, legendary composer Ludwig van Beethoven premiered his third symphony, later titled Eroica, at a private performance held at the palace of Prince Lobkowitz. The piece was written in sonata form — a traditional form for a symphony, yet the sound was unlike anything ever heard before by man. There were many reactions to this piece; positive, negative — many were even frightened by the might of sound Beethoven's work produced. But his instructor, Haydn's reaction remains truest.

Unusual. He's done something no other composer has attempted; he gives us a glimpse into his soul. I expect that's why it's so noisy. But it is quite new--the artist as the hero...Everything is different from today.

And so it was. After Beethoven's death, following another six symphonies, all of the music changed. Composers began to create works that reflected their inner turmoil, or their insurmountable rapture, instead of simply serving to please the listener with stable sounds of elegance. Many of the same composers even paid tribute to various works by Beethoven with musical motifs and little melodic or harmonic parodies (Mahler's Symphony No. 5, Chopin's Revolutionary Etude, and Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5 to name a few examples).

This was over two hundred years ago. This was the point in history wherein musicians were finally beginning to realize what this art form is and how it can be used for self-expression and even transcendence. Now, we have reached the same point in a new art form. Videogames started as little more than marketable crowd-pleasers. Titles like Braid, LIMBO, Fez, Titan Souls, and many others revisit traditions in the same way Beethoven revisited the symphony and sonata form, bringing to the public new innovations for the medium in ways both familiar and exciting.

What do you think? Are these games doing right by Mario? Are arthouse games the way of the future? Is this thesis ridiculously convoluted and silly? Sound off in the comments. Thanks so much for reading, and may the force be with you always!

Published: Oct 24, 2015 01:30 pm