This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Resident Evil series, which is easily one of the weirdest success stories in video games. Even long-time, hardcore fans of the franchise will tell you that the plot is not Resident Evil‘s high point, and I can’t realistically argue that they’re wrong.

RE started by making it all up as it went along, eventually kitbashed itself into a sort of bizarre military thriller, and then chucked it all to fight mold monsters in backwoods Louisiana. Resident Evil, as fiction, is a case of Capcom succeeding despite itself.

Twenty-five years later, however, the survival-horror franchise has become one of the tentpoles in the increasingly crowded zombie sub-genre. For all the balls-out craziness of Resident Evil’s story, it’s consistently done one thing that sets itself apart from the pack, which we as fans and critics don’t talk about enough. To some extent, I’d argue that it’s the secret to RE‘s lasting appeal.

Simply put: the Resident Evil games aren’t cynical, and that’s almost entirely unique within the genre.

Editor’s note: Spoilers for the Resident Evil series, including Resident Evil 2 Remake, follow.

Mission Statement

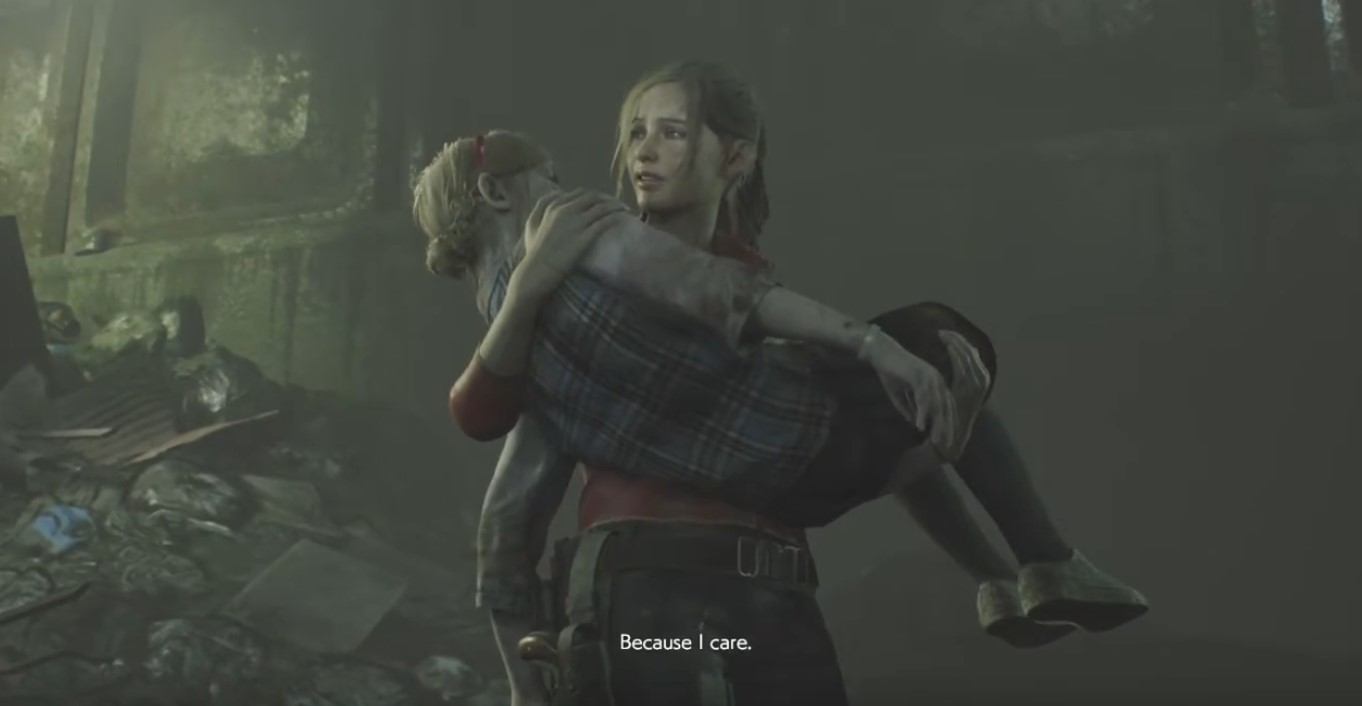

The best and most useful example of this, which has stuck with me since I saw it, is from the 2019 Resident Evil 2 remake, right after the crane fight in Claire’s scenario, when you catch up to Sherry Birkin in the drainage room.

Sherry’s been infected with the G-Virus offscreen, which, as far as we as players know, is a death sentence. Even Sherry’s mother, Annette, writes her off as a lost cause.

Claire, however, does not, which leads to the following exchange:

CLAIRE: Sherry, don’t worry. I will get you whatever you need, OK?

SHERRY: Why are you doing this?

CLAIRE: Because I care.

This is the only explanation that you, as the player, ever get for Claire’s decision. She doesn’t have any convenient narrative justification on deck, like a tragically dead younger sibling, and doesn’t have a plan to get something out of the deal. Claire has every right to walk away from this, but chooses to give a damn about this girl she just met.

In a lot of other zombie media, this scenario ends with one or both characters dead, because you can’t have nice things during a zombie outbreak. If this were any version of The Walking Dead, Claire would have dropped from a sudden headshot out of nowhere by the time she finished enunciating the word “care.”

In Resident Evil, however, Claire isn’t punished for a moment of compassion. Instead, if anything, she’s rewarded.

Humans as Monsters

The modern zombie genre was effectively codified by George Romero’s “Dead Trilogy” of films, particularly 1978’s Dawn of the Dead (above). Virtually every zombie film, game, book, show, comic, or what-have-you since Dawn has some of that movie in its DNA, whether it’s deliberate inspiration (Dead Rising, Netflix’s Daybreak) or just reacting to it (the mall level in Left 4 Dead 2, Joe Russo’s Return of the Living Dead).

One of the primary drivers of the action in the “Dead Trilogy” is that the humans are the ones who screw everything up, and that’s gone on to be the most influential aspect of the films.

In both the 1968 and 1990 versions of Night of the Living Dead, the survivors take more damage from their own dumb decisions than they do from the zombies. In the original 1978 Dawn of the Dead, the survivors’ fortified hideout is only breached when a bunch of idiot bikers decide to break in for fun.

Over the course of the next few decades, this has slowly been codified into the bedrock of the genre, particularly in video games (i.e., Days Gone, above).

Zombies can be dangerous under the right circumstances, but in nine zombie apocalypses out of ten, it’s the humans that you really have to watch out for. They’ll make mistakes; they’ll screw you over; they’ll provide the sub-bosses while the zombies fade into background noise.

That, in turn, has given a lot of recent zombie stories an unmistakably cynical edge, if that cynicism isn’t the whole point of the story in the first place. The zombies themselves can easily end up as little more than an inciting incident, which lets a writer go on to explore a scenario about desperation, deprivation, and inhumanity.

That isn’t a criticism. That kind of story can be and has been done well, first by Romero–I basically just described 1981’s Day of the Dead–and then by 40 years of other creators.

The issue at hand is that it’s become the standard formula for the genre, which shifts one of the central questions of the narrative. Instead of asking, “Will humanity survive?”, the zombie apocalypse is asking, “Is humanity worth saving?”

Resident Evil‘s answer to the latter question, traditionally and almost uniquely, has been “Yes.”

Canceling the Apocalypse

You can make the counterpoint here that what Resident Evil is actually saying is, “Humanity will survive because we, Capcom, want to keep making Resident Evil games.” That’s entirely valid, particularly as a “Doylist” interpretation of the series.

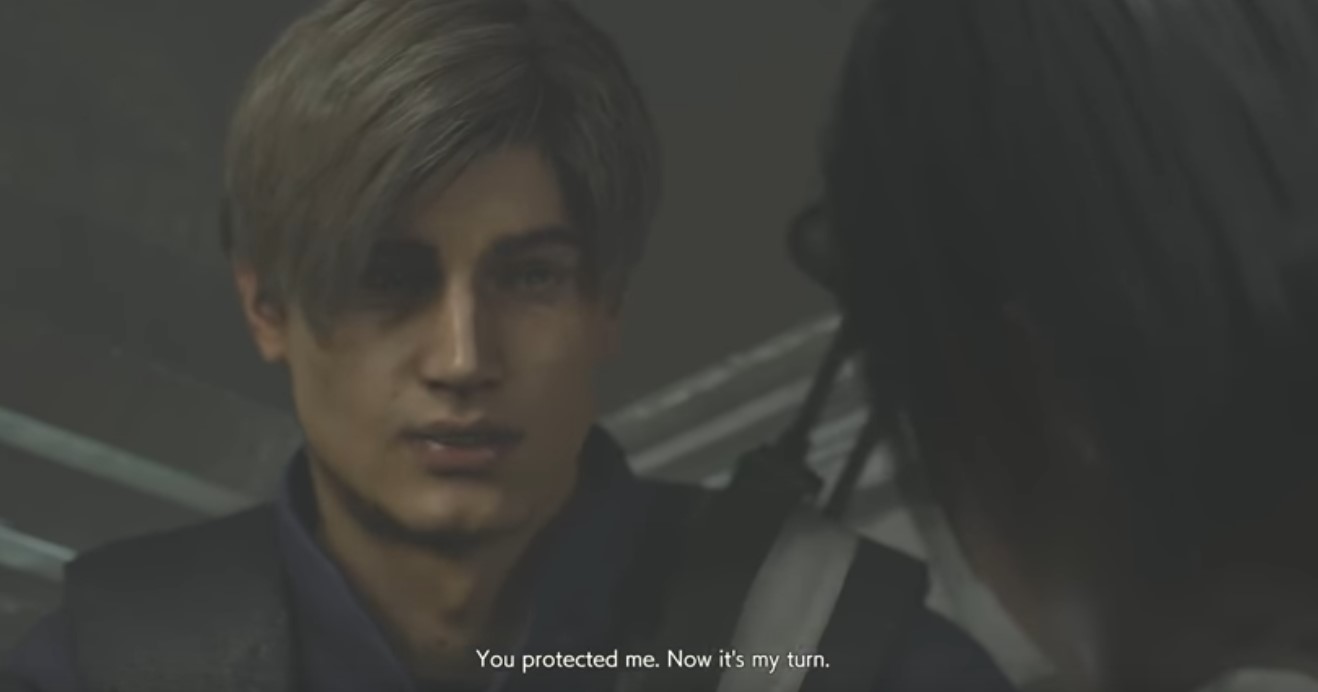

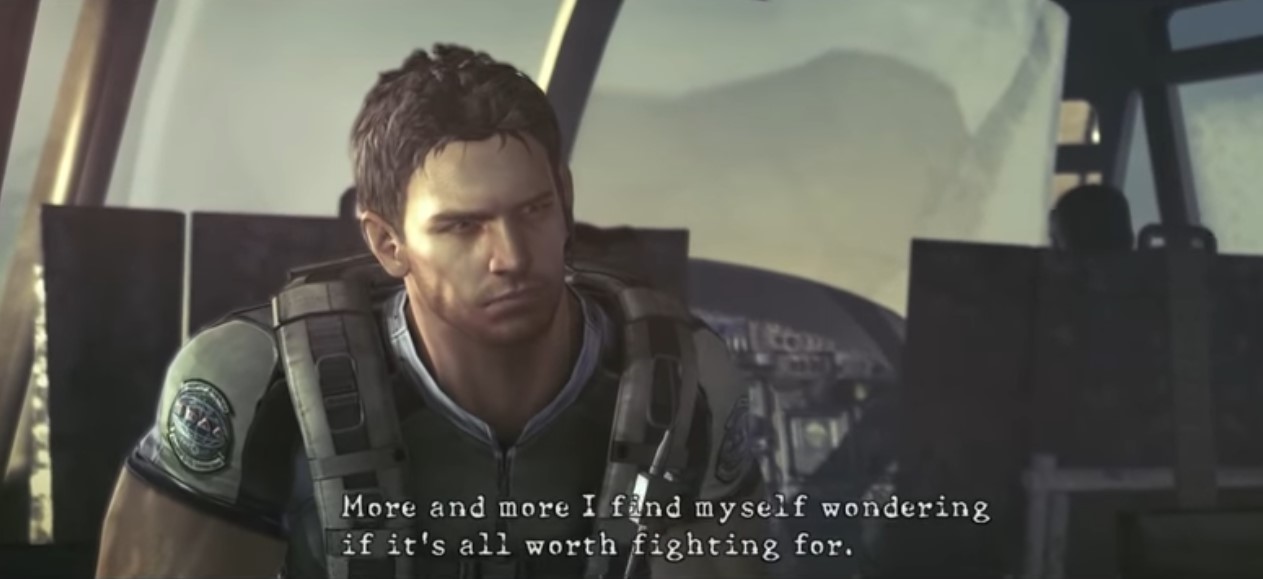

It’s also worth noting that the series’s main characters, particularly Chris and Leon, have been put through the wringer. Chris is visibly burned out at the start of Resident Evil 5, then spends most of Resident Evil 6 as a post-traumatic wreck. Leon is an outright drunken mess in 2017’s Vendetta.

There’s a difference between the characters suffering from bouts of cynicism, however, and the series itself falling into that trap.

In fact, one of the abiding themes of the series, both in gameplay and in the last few mainline games, is persistence: in continuing onward, regardless of the odds, to try and achieve the most positive outcome that can be hoped for under the circumstances.

The world of Resident Evil is one in which atrocities happen regularly, usually for astoundingly dumb reasons. Whether it’s Wesker’s planetary eugenics plan in RE5, Glenn Arias’s revenge scheme in Vendetta, Morgan Lansdale endangering the world to save it in Revelations, Alex Wesker’s epistemologically-questionable resurrection scheme in Revelations 2, or the hundred clashing motivations you get from various Umbrella employees throughout the series (money! power! a kingdom in Africa where only pretty people get to live!), the world of Resident Evil is in a constant state of catastrophe.

It’s never quite reached that point, however, because the villains tend to lose. They don’t turn circumstances around to somehow benefit from them, and they don’t slink off with no permanent damage like the Joker to menace the heroes again in the next installment. (Usually. Some of them are still around.) They’re confronted, they’re fought, and they’re taken out, one way or the other.

Granted, those victories don’t come cheap. Whether it’s a friend, a team, a town, or a city, you don’t hit the closing credits in Resident Evil without the protagonists paying dearly for it. This is still a horror franchise, and not everyone gets to make it out unscathed.

Occasionally, you don’t get to have any real victory at all. For example, neither version of Resident Evil 3 gives Jill much of a chance to do anything besides survive, and Resident Evil 6 relies heavily on hopelessness as its primary horrific theme, so all you get to do for most of it is helplessly watch people die. (Like a lot of things about RE6, it’s not a bad idea, but the execution isn’t there.)

It’s still a far cry from many of the other games playing in Resident Evil‘s genre-pool, many of which start at the end of the world. You spend a lot of time in those games fighting other humans over relative scraps, for the slim chance that maybe the next day will be marginally less awful than today.

In Resident Evil, on the other hand, the world is worth fighting for, is being fought for, and those fights are successful a surprising amount of the time. Some humans are bastards, but some are selfless enough to keep showing up to fight them, time and time again, regardless of the personal cost.

For whatever reason, that’s become the primary factor that sets Resident Evil apart from everything else. It’s the one major franchise in the zombie horror genre where hope actually matters and victory is possible, if costly. It deserves more credit for that than it’s ever gotten.

[Image sources: IMDB, Capcom]

Published: Apr 30, 2021 01:12 am