Digimon might remind themselves they’re the champions every time an episode of the Digimon anime played on American television, but the truth of the matter was quite a different story for a long time — and still is, to an extent.

Despite technically being born before their much better known rivals, Pokemon, the digital beasties never enjoyed the same reputation in the West. A big part of that is down to timing and marketing, but there were plenty of production issues involved as well.

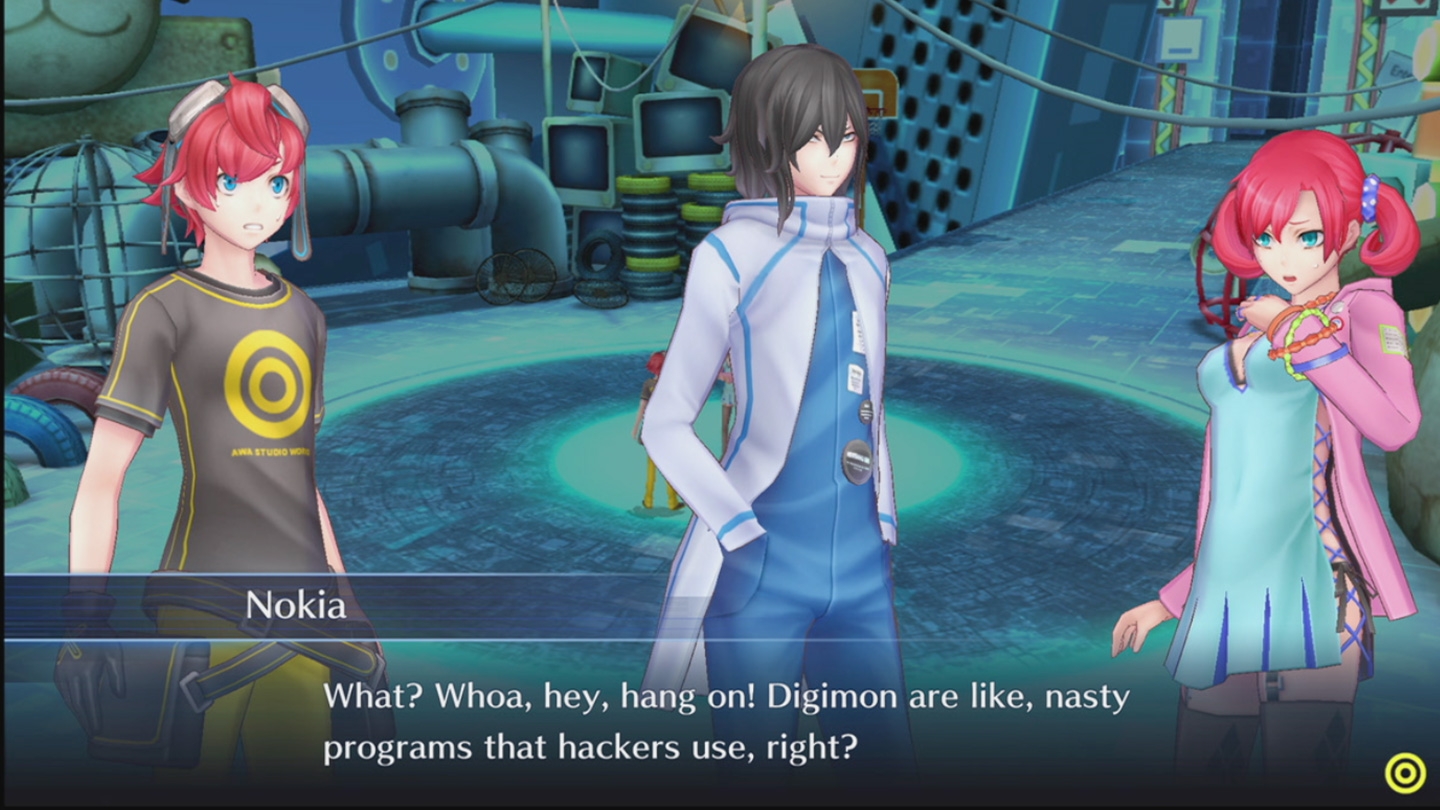

In fact, it wasn’t until 2016 saw Digimon Story: Cyber Sleuth release in the West that the franchise attained anything resembling coherent design and cohesive originality. Now that it has, though, all signs point to the franchise hopefully remaining unique and a presence in the West for years to come.

It Starts with an Egg

Digimon started life, ironically, as a pocket monster franchise, literally. It was one of those little monster-raising things you keep in your pocket — the ones we all got in trouble with at school because it was more interesting than school.

From the start, it emphasized training your digital monster and helping it grow, not necessarily attached to any kind of story.

The first Digimon video game was a little ditty titled Digital Monster Ver.S: Digimon Tamers (not to be confused with the third season of the anime) on the Sega Saturn in 1998, which functioned basically as a TV-oriented conversion of the virtual pet. This entry has been lost with time, a bit for good reason. It didn’t hold a candle to Pokemon‘s RPG offering, which released a full two years prior in the region.

The series’s first full-fledged video game outing, Digimon World, didn’t make it West until 2000, leaving Pokemon to begin its course of cultural domination with a multi-pronged media approach centered around video games and anime a full two years prior in North America. Pokemon had won.

And it’s not too surprising that Pokemon succeeded. Red and Blue are rather simple by today’s standards, but they wrapped up monster catching and raising in a more interesting package. Instead of just waiting for your Pokemon to poop and grow, you could take it on an adventure, stick with it for as long as you wanted or shelve it for a newer ‘mon, and then win the ultimate challenge against the Elite Four.

All this was a huge hit, despite the slightly misleading premise in Pokemon‘s core mechanics. You really don’t “train” your Pokemon in the same sense you would train your Digimon. Yet along with the more attention-grabbing adventure elements, the Pokemon anime got a two-year head start as well, so when Digimon caught up, it could only be perceived as an inferior contender.

After all, a franchise that defines itself by claiming it’s better than something else clearly doesn’t have as much to offer, right?

The World is Your… Farm?

Earlier Digimon games didn’t do much to emphasize the series’ foundational features and dispel that idea.

Tell that to a die-hard Digimon World fan, and you’ll be quickly educated on how wrong you are, but that’s sort of the point here. Digimon was confined to “those people” on the other side of the playground. While it was dearly loved by the ones who did take a chance on the copycat monsters, the developers went about setting the franchise apart in all the wrong ways.

The original PlayStation Digimon World games were a hodgepodge of genres and mechanics that work well when they do work, but lack clear direction. From recruiting people to a city to completing random mini-games, engaging in fights, and doing some 3D exploration, they offer a bit of everything without perfecting any one thing.

In that sense, you could say Digimon World was ahead of its time, with the genre blending and more open-ended sense of play.

It’s a shame, then, that the micromanagement aspects of Digimon raising held it back. Waiting for your Digimon to do its digi-doody when it lives in a small piece of plastic inside your pocket is fine because you can do other things. Waiting for it as a form of entertainment whilst sitting in front of the TV is another matter entirely.

Meanwhile, Pokemon was off refining perfection with Gold and Silver, offering an improved — and much more focused — experience that also had the major benefit of being handheld.

That hit Pokemon‘s target audience the most, since Nintendo’s handhelds were always marketed towards younger gamers, while the franchise was still one of the only games of its kind. Digimon was overshadowed not just by Pokemon again, but by other, more innovative and rewarding, PlayStation era games too.

Mimicry, Flattery, and All That

Fast forward through several years and past some more Digimon spin-offs, and we get to the point where Digimon made it back to gamers’ pockets — and deserved the aspersion hurled at it that it was just a copycat franchise.

Digimon World DS followed a pattern very similar to Pokemon. You get pulled into a new world, meet a professor-type person (well, digital monster in this case) pick a starter Digimon, and travel around fighting and training monsters. Leveling up the Tamer rank is equivalent to getting a Gym Badge, and it’s all just too familiar. That fact wasn’t lost on fans and critics alike when the game launched in the West.

Granted, a lot of this was still very Digimon. Raising and training via managing the Digi-Farm, Digivolving, and thoughtful management all played a vital role in progressing through the game. In fact, Digivolving is one of the things that really set and continues to set Digimon apart from its better-known rival.

Where evolving a Pokemon is fairly straightforward, Digivolution employs a less hardcore version of Pokemon‘s IV training. Focusing on a specific stat or meeting some other requirement allows a Digimon to change form, and knowing when to Digivolve or not has always been part of the series’ main gimmicks.

However, there just wasn’t enough to make it worthwhile in World DS. The difficulty is very low, with no option to change; the story is non-existent; and the localization is appalling.

Its sequel mimicked Pokemon even more, splitting the game into two versions — Dawn and Dusk — with different monsters and slightly different dungeons. Yet it also diluted the experience with endless fetch quests and lower production values.

It says something when a set of games considered mediocre like the DS Digimon World games is simultaneously praised for being the best in the franchise.

Timing was another issue here, and again, it stayed in Pokemon‘s shadow,. The first World DS game was three years too late with mechanics and ideas Pokemon‘s Gen III implemented.

Dawn and Dusk released in the same year as Pokemon Diamond and Pearl, The former were iterating again on a now four-year-old formula with little to show for it, while the latter launched Pokemon into a completely new audience with IV stats, a focus on the meta-game, and vibrant new graphics.

A Long Intermission

Unfortunately, North American video game sales figures aren’t made widely available. Marketing research firm The NPD Group publishes monthly and yearly Top 10 style lists of sales for hardware and software, and that’s about it.

There might not be any reliable statistics for how the Digimon World DS games sold in the US, but we can safely assume they didn’t do very well at all.

Why? Because localization for Digimon games from then on was spotty at best, with the West only getting random titles like Digimon World Championship. That was a shame for Western fans and potential newcomers to the series, because 2008-2013 saw Digimon games of much higher quality release in Japan.

Notable highlights include Digimon Adventure for the PSP that basically lets you play the anime and the successful Digimon World Re: Digitize, which, in Japan, garnered first week sales just 10,000 shy of Pokemon Black 2 and White 2‘s first week numbers.

Alas, Western gamers languished with no Digimon to hope for in the near future — or rejoiced, depending on your experience with the games up to that point.

Jumping Back Into the Future

Those two games in particular started a trend that would carry over to Digimon Story: Cyber Sleuth and its sequel, namely trying to forge a unique identity and create a unified set of mechanics.

Cyber Sleuth builds on the longtime series staple of existing alongside a digital world by taking it further, blending the concept with ideas and situations specific to the mid-2010s.

No longer is the idea of vanishing inside a computer meant to be enough of a draw. Instead, people live through and in EDEN, a virtual reality city that — in a nod to the problems of online socialization — lets you completely recreate yourself and hide your real identity.

This brief and simple setup immediately sets the game apart from its rivals. Accusations of copying certainly couldn’t be leveled at Digimon here, particularly since it has Sword Art Online beat by many years in the “entering a digital world” department.

More importantly, Pokemon continued to offer more of the same (since that’s what people wanted), leaving fans wishing for something more “mature” or at least something more ambitious in the story department.

Cyber Story delivers on both counts, drawing on Digimon‘s origins of a monster-based series in a super-modern world to finally set the series apart.

It’s been called Persona-lite, with its modern setting and emphasis on relationships, and that’s not really a bad thing.

From cyber-crime syndicates to malicious hackers and all manner of problems in between, the world of Digimon Story is a vibrant place that, despite being fictitious, still manages to resemble the real world in some ways. The story doesn’t hit Persona‘s level of maturity, but the story beats, darker elements, and bits of intrigue and mystery are still not something we’ve seen or are likely to see in Pokemon, let alone something a Digimon game has ever tried to do before.

Having a solid story, something that compels you to progress through the game, gives you a reason to raise your Digimon as well, and it gives the monsters more significance than just being something to collect.

It’s helped along by a couple of other factors too, though.

The first is the difficulty. On default, Cyber Story is somewhat easy, but the difficulty level can be bumped up to accommodate those with different needs. That the game makes allowances for different playstyles is another first for the series and something Pokemon still hasn’t done.

Masters of Digi-volution can probably still steamroll through the game by min-maxing stats in their Digi-Farms and breaking the game through skillful control of their monsters. Newcomers can take it easy with normal difficulty or take on a greater challenge as they try to learn the ropes.

Making Digi-volution so important to progressing through the game adds a much greater, and much needed, sense of cohesion when combined with the improved story elements. There’s a clear goal for raising a Digimon and an easy-to-understand path for getting there, whether you want that extra power or you need to crush a boss.

Sure, it’s something the World DS games had, but there’s no denying it’s much more enjoyable when you feel like you’re doing these things in a unique game instead of a game that just acts as a bridge to the next Pokemon. Equally as important, it was the first time in nearly two decades Digimon‘s traditional mechanics of raising and evolution finally got packaged together as something you could reasonably call fun.

Finally, there’s combat. Pokemon was never overly simplistic in its numerous type match-ups, and for those who didn’t grow up with a type chart permanently seared into their brains, things like Ice > Flying > Grass >Fire > Ice are something of an entry barrier.

Not so with Cyber Story. A few basic types, a few more subtypes, and that’s it.

The Final Results

So, Cyber Story had interesting characters, forged a unique identity, doubled down on making the mechanics fun and worthwhile, and finally had the means to leave Pokemon‘s shadow. But did it work?

Yes and no, but mostly yes. Timing, again, has a lot to do with why Cyber Story was received well.

How well is somewhat relative, though. The game came West in 2016, the same year as Pokemon Sun and Moon made their appearance. But this time, Digimon was on the Vita, which reached an entirely different market than the 3DS.

These were often the people who grew up playing Pokemon and wanted something different, and by 2016, Vita owners were already starting to see the handheld console’s slow death on the horizon, noticeable first and foremost by a steady drought of new games. A new monster-collecting game promising a hefty bit of content and darker story wasn’t something to miss, even if it was digital-only in the West.

And that’s important to understand. Cyber Story didn’t break the top 20 PS4 games in the months following its release in the West, but consistently remained in the top 5 Vita games.

The same went for its sequel, Digimon Story: Cyber Sleuth — Hacker’s Memory when it released a few years later. In fact, Hacker’s Memory was 2018’s top Vita game, and that isn’t taking into account the Asian-with-English-subs versions available for import.

Yet it didn’t appear on the PS4 lists again, and Pokemon continued to dominate the handheld titles.

—

With data like that, it probably seems a bit disingenuous to say Cyber Sleuth was a major turning point in the Digimon video game franchise. However, context is everything here.

The Story games were still handheld hits, far surpassing the DS World games in both popularity and quality. Quality is the most important point here, though, as this is the stage when finally — finally — Digimon got its act together in a sensible, focused game.

It’s not known exactly how well the games did perform, but it was enough to reverse the localization curse. It convinced the series’ producers to continue with the Story subset of Digimon games and ensure future games in the Digimon franchise were localized for Western audiences.

It’s even the reason we’ll be getting Digimon Survive (whenever that happens). If that isn’t a turning point for a franchise once considered a sad, desperate copycat, I don’t know what is.

Published: Jul 17, 2019 7:28 PM UTC